|

Tacitas or cupules? an attempt at distinguishing cultural depressions at two rock art sites near Ovalle, Chile. Maarten van Hoek vanhoekrockart@parelnet.nl

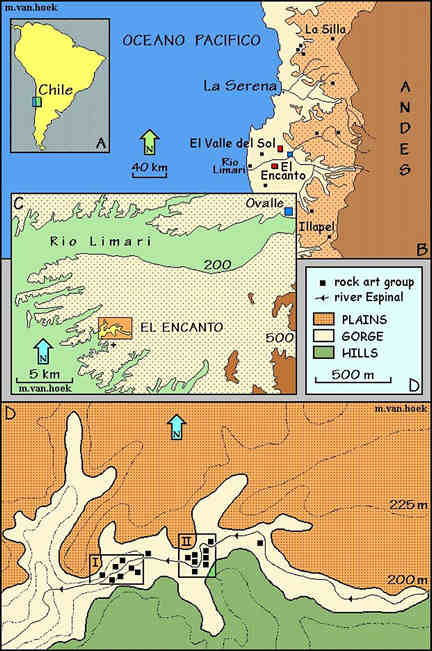

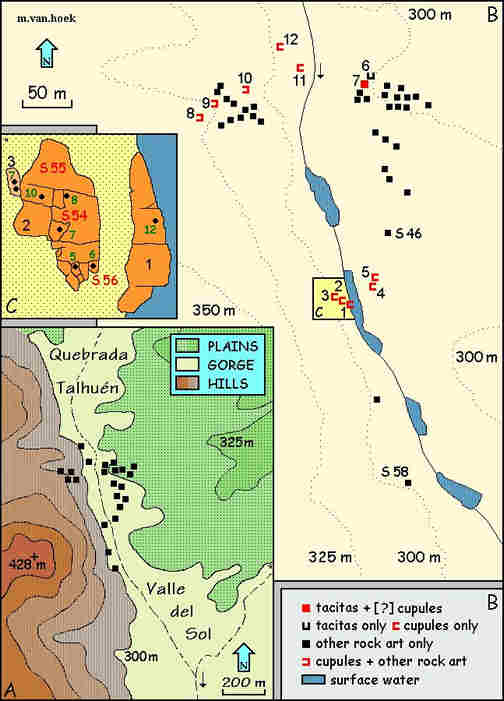

Introduction About 50 years ago, there hardly was any record of prehistoric rock art in the north of Chile, South America. Up to date however, a wealth of geoglyphs, petroglyphs and pictographs is known to exist. Well known are the impressive geoglyphs on the hillsides of the lowland valleys of Azapa and Lluta near Arica (Van Hoek 2002a; see also my web pages at: Arica) and the field of petroglyph boulders near the oasis of Tarapacá in the middle of the Atacama. Also the artistic variation in this area is enormous. In the heart of the Atacama Desert, at Cerro Unita, is the approximately 100 metres high geoglyph of a human figure, possibly representing Wiracocha or Mallku Tarapacá (Chacama & Espinosa 2001), while 20km further SE we find small petroglyphs of humans, birds, felines and camelids engraved on the knee-high boulders of Tarapacá 47 (Van Hoek 2002b; see also my web pages at Tarapacá). Much further south, in the semi-desert around Ovalle, a rural town in the Coquimbo Region (Figure 1), impressive petroglyphs of human figures and "masks" appear on large boulders in secluded valleys. The same area is also well known for its rocks with large artificial depressions, often bowl-shaped and looking like mortars, described in Chilean literature as "Tacitas". Such "Piedras Tacitas" occur at several archaeological sites in the Coquimbo Region, especially in the coastal area where they often co-occur with prehistoric shell middens (Gallardo Ibáñez 1999: 35). However, "Piedras Tacitas" are also found together with prehistoric rock art in the area around Ovalle (Figure 1). The most important site, where both "masks" and numerous "Tacitas" occur together, is El Encanto, a small valley full of rock art, discovered in 1949 and fortunately a guarded National Monument since 1979. It is situated 20 km SW of Ovalle (Figure 1B). Three satellite photos indicating the location of the rock art sites of the Ovalle area can be seen at my web pages (Ovalle).

Several researchers have described the many hundreds of iconic and non-iconic figures and "Tacitas" at El Encanto (Iribarren 1949, 1954; Klein 1972; Ampuero & Rivera 1964, 1971; Ampuero 1993) and El Valle del Sol (Van Hoek 2000). Regrettably but understandably, most of the works describing the rock art at El Encanto mainly focus on the impressive anthropomorphic figures and the enigmatic "masks" (Figure 2). "Tacitas" are only marginally discussed, although the importance of those cultural depressions is acknowledged.

However, during my survey in the Valle de El Encanto in July 1999, I noticed that there were quite a few rocks, officially listed as "Piedras Tacitas", that actually also featured true cupules, without, however, any published work classifying these depressions separately as cupules. Those depressions were considered small "Tacitas" or unfinished examples. Some stones listed as "Piedras Tacitas" did not even have "Tacitas" at all, but only featured cupules instead. During the next survey, in July 2000, my wife Elles and I were able to examine another series of (previously unpublished) rocks with only cupules in El Encanto. Also the Valle del Sol, a similar but lesser rock art concentration about 10 km NW of Ovalle (Figure 1B) was re-visited in July 2000, in order to check if a similar situation occurred there as well. Indeed, also at El Valle del Sol we recorded more cupule rocks (Van Hoek 2000). All these new finds and the notable differences between "Tacitas" and cupules justify a thorough review of the two types of hemispherical cultural depressions. The specific purpose of this paper is to establish that the two types of anthropic depressions occurring around Ovalle are indeed two completely different cultural manifestations. Most likely all "Tacitas" are utilitarian of character and may therefore not be regarded as rock art, whereas the enigmatic cupules may constitute a distinct class of rock art. Also the spatial distribution of the two types of depressions will be discussed in this paper.

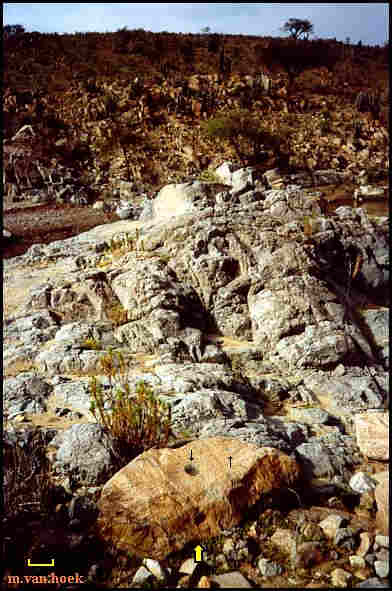

The physical environment The rock art sites of El Encanto and El Sol are situated in small side valleys of the River Limarí that runs west and down from the high Andes to the Pacific Ocean (Figure 1B). The landscape generally consists of hills and low mountains interspersed with flatter parts of sedimentary rock and/or drift material. As is often the case with rock art sites in the arid or semi-arid areas of Chile, El Encanto and El Sol are situated in one of the many Quebradas (gorges) that have been cut out by the erosive forces of rivers. According to Ampuero (1993: 5) this happened at El Encanto about 50.000 to 100.000 years ago. Especially in the upper part of El Valle de El Encanto enormous blocks of granite thus became exposed by the river Espinal (Figure 3) and it is this reddish granite that offered the canvas for the indigenous groups to place their paintings and petroglyphs upon. Those groups used El Encanto and El Sol as important stopping places during their transhumance from the coastal areas to the high Andes and vice versa. At these stopping places they were certain to find shelter and water, which allowed plants and trees to grow.

The valleys of El Encanto and El Sol actually are "hidden" places. Both sites have in common that they are bordered on one side by extensive higher plains and on the other side by conspicuous hills. The hills south of El Encanto (marked + in Figure 1C) constitute the only elevation in a wide area around the site. This small range of hills not only is easily recognisable from a long distance (and may therefore have served as a point of orientation for travellers); it also offers shelter against the colder winds from the south (Klein 1972: 11). By executing their symbolism on the rocks, the naturally formed valley was gradually transformed into an important spiritual "place". According to Tilley (1994) a "place" is a specific defined topographical location at which human activity is focussed. This happened at El Valle del Sol and other sites in the area, but especially at El Encanto, which had an unusualness that set it apart from other sites and neighbouring valleys (Klein 1972: 9, 11). For that reason, only El Encanto developed into a regional focal point of major importance, which resulted in an above average and still unexplained number of "Piedras Tacitas", a wealth of sophisticated iconic art and, often neglected in rock art studies, a small range of simple cupules.

Defining cupules To avoid confusion, it is necessary to clearly define cupules, as not every cultural depression in a rock surface should be regarded as rock art. Unfortunately there is quite some uncertainty in Spanish literature about the translation of the word 'cupule'. Costas & Novoa (1993: 23) describe cupules as "cazoletas", pequeños hoyos hemisféricos de planta circular y fondo cóncavo - también conocidos como "coviñas" y "fosettes". Also the word "hoquedades" has been used (Van Hoek 1997: 37). The situation in South America is even more confusing. For example, Querejazu Lewis (1998: 48) distinguishes between "cúpulas" - true cupules, and "morteros" - grinding hollows. Other Bolivian researchers use the word "cúpulas" but make a distinction between "cúpulas auténticas" - true cupules and "cúpulas utilitarias" - grinding hollows, the latter also known as "batanes" or "moledores" (Methfessel & Methfessel 1998: 36). Chilean literature often seems to make no distinction between utilitarian and non-utilitarian anthropic depressions and labels every cultural depression as "tacita". To bring the Spanish terminology more in line with the universal term "cupule", I would like to suggest to use the Spanish term "cúpula" to indicate all non-utilitarian anthropic depressions between 2cm and 10cm, and "morteros" to indicate the larger, utilitarian anthropic depressions like grinding hollows and to avoid the word "tacita". However, in this paper the word "tacita" will be used to indicate the large cultural depressions in the Ovalle area as described in Chilean literature. Thus it will be possible to focus the discussion on the distinction between "Tacitas" and cupules. What is a cupule? In their discussion about cupule engravings from Jinmium, northern Australia, Taçon, Fullagar, Ouzman & Mulvaney offer a useful definition of the cupule (1997: 943). A true cupule is a cup-shaped non-utilitarian and definitely cultural mark that has been pecked or pounded into a rock surface. Although a true cupule never has been formed by nature, it is possible and even likely that, like in many places around the world, natural hollows have triggered the execution of anthropic (cultural) depressions (ibid. 1997: 961). Cupules normally average 5cm in diameter, but there are also smaller and shallower cupules of around 2cm, as well as larger ones measuring up to 10cm. Although most cupules are circular, they occasionally appear in oval- or kidney-shapes. Cupules occur world-wide in several (archaeological) contexts from almost every prehistoric and historic period of human history. Their meaning is often both intangible and manifold. However, cupules are not to be confused with grinding hollows that are often much larger (they may range from 10cm to over 30cm in diameter). Grinding hollows are abrasion-formed depressions (natural or cultural of origin) used for processing food, dyes or other material, whereas the meaning of cupules often remains obscure. Although many grinding hollows are circular and deep like large basins, also elongated depressions occur. Grinding hollows are not necessarily deeper than cupules; at El Encanto several rather shallow examples were noticed (Figure 6, blue arrow). Another distinction is that cupules may appear on horizontal, steeply sloping and vertical surfaces and on large and small outcrops or boulders alike, whereas grinding hollows almost exclusively are found on rock surfaces that are horizontal or nearly so. In essence, also the "Tacitas" near Ovalle appear to be grinding hollows or mortars. They are often very large and average 15cm in diameter (ranging from 10cm to 40cm) and usually are strikingly deep. Although most "Tacitas" are perfectly circular, there are quite a few oval and rectangular shaped basins (and these usually are rather shallow and may have had different origins or functions). Another characteristic of "Tacitas" is their smooth appearance; clearly they have been abraded or polished either by executing them or by using them for whatever reason. Most "Tacitas" appear on large surfaces that are horizontal or nearly so. Some smaller stones with "Tacitas" also occur and only one example (rock 4 in square F6, Figure 5) is severely tilted. This exceptional position however, may have been the result of natural forces like earthquakes, torrential rains or even lightning (Sven Ouzman 2002, pers.com.). The differences with cupules are too obvious to uncritically classify the cupules of El Encanto as small "Tacitas". There are also several reasons to refute the idea that all cupules are unfinished "Tacitas", as Klein (1972: 103) suggest for smaller cupule-like depressions at the most elaborately engraved "Piedra Tacita" in El Encanto (his E-28a; my number 10 in Figure 7). The most obvious reason is that some stones with cupules are actually too small to offer space for a "Tacita" to develop, especially the smaller dome-shaped rock with only one cupule on the rounded top. Another reason is that there are some rocks where cupules are clustered too close together to allow space for one of them to develop into a basin. A third reason is the appearance of true cupules on vertical rock surfaces. And last but not least, why ignore the possibility that cupules have been manufactured as a separate petroglyph tradition in this long-inhabited area? In my opinion, some cupules may have preceded the "Tacitas"-tradition. It is even conceivable that the presence of cultural cupules triggered the execution of "Tacitas", although the role of natural depressions may not be ruled out. Although it can never be proven, it is also possible (and even quite likely) that "Tacitas" replaced some cupules. As the focus in this paper is on cupules, it has not been attempted here to differentiate between the several types of iconic (see Klein 1972) and non-iconic art, both of which are labelled as "other rock art only" in this survey and on the maps. On the contrary, it was considered more important to distinguish between "Tacitas" and cupules and whether these depressions appeared in combination or singly. Although we have surveyed most of the "Piedras Tacitas", there remained an element of doubt whether all "Piedras Tacitas" only had basins or were (once) combined with cupules. Some stones were covered by earth or were overgrown; a few were untraceable. Also, in some cases "Tacitas" may have replaced cupules. On the detail-maps, these doubtful examples have the same symbol as the stones where "Tacitas" are definitely combined with cupules.

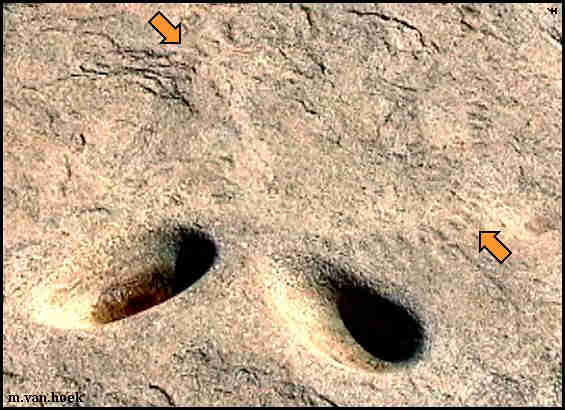

A possibly important and intriguing aspect of the rock art in this valley is that never a combination is found on any one "Piedra Tacita" with the standard forms of the "other rock art", like anthropomorphs or "masks". Cupule stones also seem to have been avoided by other types of rock art. There are two exceptions. In one case (rock 3 in Figure 5; possibly E-44a) we found many "Tacitas" and a small number of cupules together with one enigmatic ring (about 50cm in diameter) of short, radiating grooves of much worn character. This design is unique to the whole area. The area enclosed by this ring of short radiates (Figure 4, between the two orange arrows) may have functioned as a culturally defined space, especially reserved to receive the product of the two grinding hollows that adjoin it. There is one other notable exception at Stone 2 in Zone II. There we find some cupules (but no "Tacitas") next to iconic rock art. For the rest cupules always appear singly, or only in combination with "Tacitas".

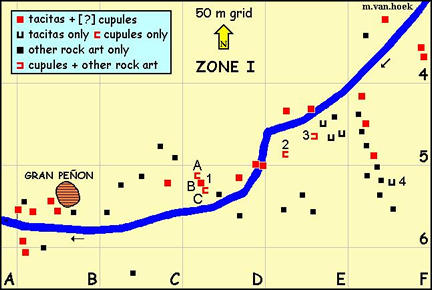

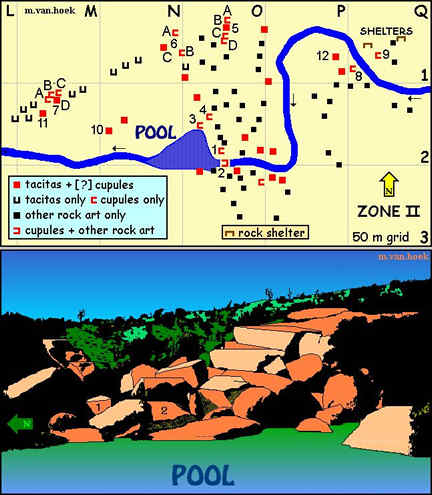

The cupule rocks of El Encanto The rock art at El Encanto is, apart from a few outlying engraved rocks, heavily concentrated in two Zones (numbered I and II in Figure 1D, and shown in detail in Figures 5 and 7). I created those two zones as they are distinctly spatially separated. A large stretch of land divides the two zones without neither notable rocks or rock art. Zone I, dominated by an enormous boulder called El Gran Peñon, is situated at lower altitude near the west end of the valley where the river exits through a rather narrow gorge. Moreover, Zone I has fewer engraved stones and the iconic art is less impressive, whereas Zone II proves to have been the major focal point of the area, as it features the great majority of the engravings and also the most sophisticated designs. Although it is clear that the art in both zones is definitely associated with the river Espinal, it must be noticed here that the course of the river may have changed during the ages, especially in the wider and flatter parts of the gorge. I will return to this aspect later. I hesitated to use the old E [Encanto]-numbering used by Klein (1972) in this paper, as these E-numbers were not assigned consistently. In some cases the whole rock with several petroglyphs was assigned only one E-number; in other cases each individual petroglyph was given a separate E-number. Although the old E-numbering appears in paint on most of the rocks, the E-numbers are often indecipherable. Moreover, quite a few new unnumbered cupule rocks were located during our surveys. Also the new numbering by Ampuero (1993) did not take in all the engraved rocks. I therefore decided to use my own numbering on the distribution maps in this paper. Only in a few cases I will state the old E-number used by Klein (1972) for easy reference.

Zone I Also in Zone I the art is clearly focussed on the river. Only at squares F5-F6 (Figure 5) there is a string of decorated rocks running uphill. Possibly it lines a mostly dry river course. Most of the other "Piedras Tacitas" are clearly associated with the river Espinal. A few "Piedras Tacitas" are actually located in the present-day stream, but this position need not reflect the prehistoric situation.

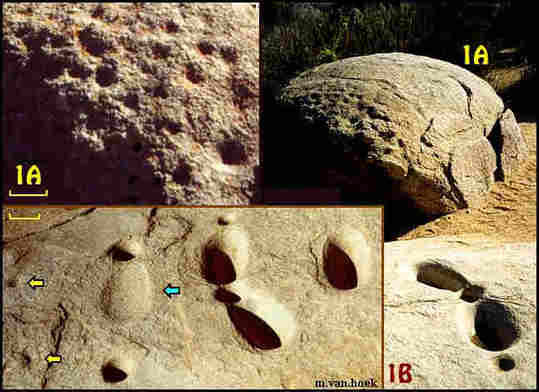

Cupule stones are scarce in zone I. We could spot only one small flat stone with one large cupule (rock 2 in Figure 5). It just possibly could have been intended to become a "Tacita". More importantly, there are two rocks with true cupules only (in square D6 in Figure 5). A medium-sized (roughly 160cm wide and 100cm high) rounded boulder (with E-50 painted on one side, but numbered 1A by me) has one distinct cupule carved on its top and a large number of worn cupules (from 4 to 8cm in diameter) heavily clustered on its rough south edge (Figure 6), but clearly spatially separated from the single cupule on the top. There are no "Tacitas" on this boulder, although there is plenty of space on its flat top. The boulder heavily suffers from exfoliation (a common weathering process of granite), and, as we shall see, this possibly forms a reason for the execution of the cluster of cupules.

Flush with the ground and roughly one metre to the SE of 1A lies a horizontal slab, numbered 1B by me, with four large oval "Tacitas", one rather shallow (Figure 6, blue arrow) and four smaller circular ones. This stone also features two cupules, 6cm in diameter (yellow arrows). Again 1m to the SE, my wife Elles noticed three small cupules (all 4cm in diameter) on the almost vertical SW facing flat surface of a smaller boulder (1C). The cupules (8 to 11cm apart) are set in a triangle, only 40cm above ground level. There are no "Tacitas" on this boulder, nor can it ever have been the intention to develop a "Tacita" out of one of these cupules. An interesting aspect of both rocks 1A and 1C will be discussed further on.

Zone II About 400m further east is the beginning of zone II (Figure 7). This area offers more interesting information regarding the distinction between "Tacitas" and cupules. Three sub-zones may be distinguished. The first sub-zone features a linear group of "Tacitas" and cupules, stretching SW-NE for roughly one hundred metres (from square L2 to O1 in Figure 7). The second sub-zone is centred on two rock-shelters at Q1, and last but not least there is sub-zone II.3 (named the "Santuario" by Klein 1972), which stretches from O1 to O3.

Sub-zone II.1 The most striking aspect of this group is the absence of "other rock art" elements, like "masks", anthropomorphs and non-iconic elements. This anomaly may be related to the linear character of the group and this phenomenon may have a special explanation, to which I shall return further on. Some "Piedras Tacitas" in this sub-zone have the odd cupule (one, rock 11 in Figure 7, also seems to have a number of roughly parallel (natural?) grooves).

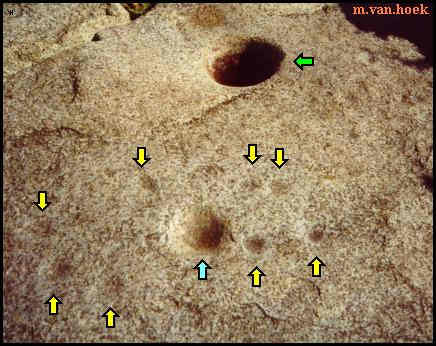

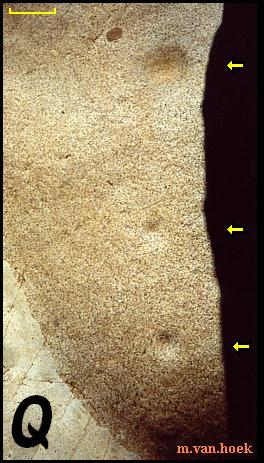

However, one group (numbered 7A to D) in this row is most interesting. Two adjoining horizontal flat stones (site 7D; old numbering E-26) have five "Tacitas", but also feature some definite cupules: at least six cupules (and faint traces of more; yellow arrows in Figure 8) of different sizes (but usually rather small) on the east slab, and one on the west slab. What makes this group interesting, however, is a (natural?, cultural?) row of three boulders just north of 7D. One small rounded boulder (7C) has two weathered but definite cupules on its top (Figure 9, blue arrows).

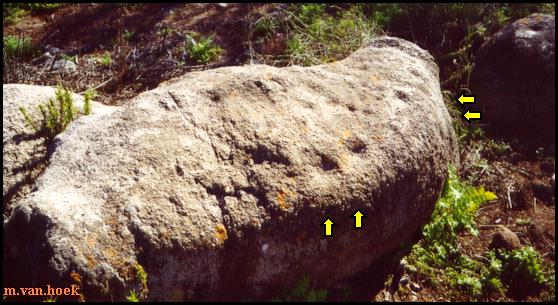

Its larger neighbour (7B) has at least seven cupules on its rough, horizontal top (Figure 10) and may be more traces of cupules plus four possible cupules on its south facing vertical face.

Immediately west of 7B is a longish boulder (7A) with two definite cupules on its crest and possible traces of others (Figure 11). Especially 7A and 7C are not suitable to ever have been intended for "Tacitas".

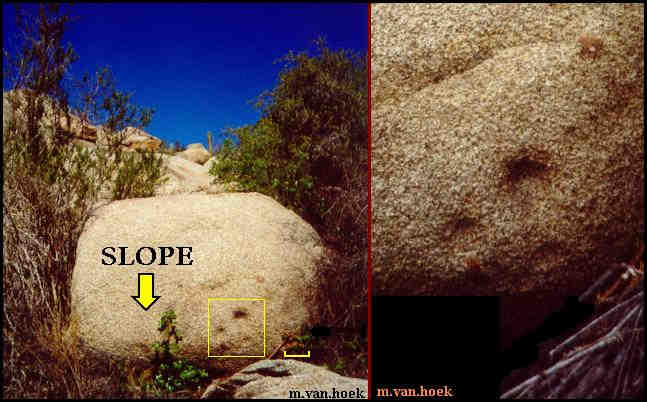

Near the east end of sub-zone II.1 is a more dispersed group of "Piedras Tacitas" and cupule stones. Rock 6C (E-22) is horizontal and flat and bears the typical "Tacitas" plus four possible cupules. But rocks 6A and 6B nearby are again small and rounded boulders, each with one definite cupule on the top. Other similar stones near this group also show traces of one or two worn cupules. None of these smaller stones will ever have been a suitable candidate for a "Tacita". A situation similar to group 7 is found at the east end of sub-zone II.1. Here, group 5 (which may as well be considered to be the north end of sub-zone II.3) comprises a linear setting of cupule rocks lining a path leading to the river. This path may have developed from the many tourists that visit the site, but it equally may be very ancient. Most conspicuous is a flat horizontal slab (5B in Figure 7; E-28a) with three "Tacitas" and one cupule of 5cm in diameter. Only 2 metres north of 5B is a small flat boulder (5A) with one definite cupule, whereas some 10 metres to the south are two small rounded boulders, one (5C) with a faint depression on top; the other (5D) with a small but definite cupule on its west slope. Especially 5D is not suitable for a "Tacita".

Sub-zone II.2 This area is interesting for its two "abrigos" or rock-shelters of huge granite boulders. Interestingly, a small boulder (or the top of a larger one) is embedded in the path leading from the river to "abrigo 2" and to a huge granite boulder with a large anthropomorphic figure that overlooks the small boulder (9 in Figure 7; possibly E-2a). On its rounded top are the worn remains of at least five cupules (Figure 12). The largest cupule is 7cm in diameter. The position of this boulder in the path may be significant, as most likely the path is very ancient.

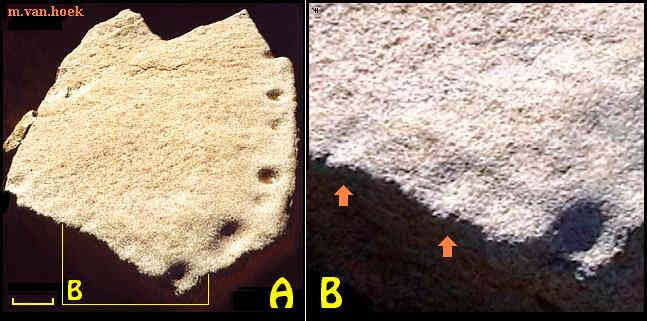

On the other side of the river and part of a cliff-like tongue of rough outcrop land is a medium-sized block (100cm wide) of coarse granite (rock 8 in Figure 7; possibly E-3) on which my wife Elles noticed three cupules. The largest cupule measures 8cm in diameter. The cupules form a triangle (compare with rock 1C in zone I) on its vertical, east-facing surface, also near the lower edge of the stone (Figure 13). Again, this is a most unlikely place for a "Tacita". It may be significant that this boulder overlooks the river and simultaneously the path to "abrigo 2" and its cupule rock (and also "abrigo 1"). A large rock with "Tacitas" to the NW (rock 12) has also a few cupules.

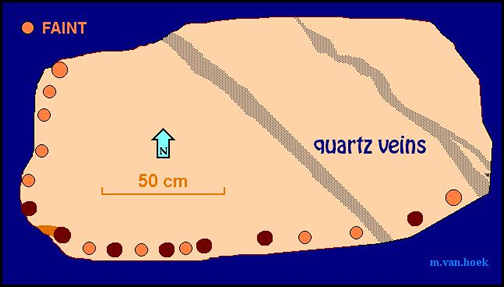

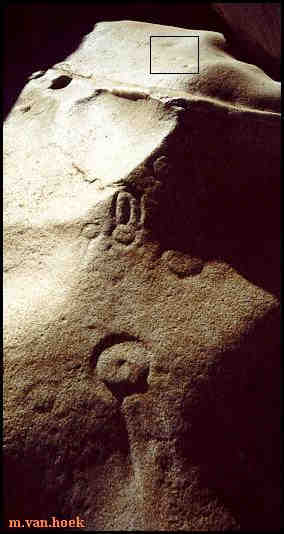

Sub-zone II.3 Here we find the biggest and most important concentration of rock art, mainly comprising anthropomorphs and "masks". However, the basic premise, resulting from my observations at Zone I, is repeated in Zone II: there proves to be a strict spatial separation of stones with "Tacitas" or cupules and stones with other types of rock art. Only in one case there is a combination on one stone of cupules and other types of petroglyphs. This rock will be fully discussed further on. It may be significant that most of the "Piedras Tacitas" and the cupule rocks of sub-zone II.3 seem to border the heavy concentration of rocks bearing "other rock art". Already described are the small cupule rocks at groups 5 and 6 at the north end of this sub-zone. Two similar stones (3 and 4 in Figure 7), each with one worn cupule on their rounded tops, were noted by my wife at the "entrance" to the jumble of huge rocks that I prefer to call the "cascade". The river runs through this chaos of tumbled rocks and flows into a rather deep pool immediately west of it. There is a strange aspect about this pool that will be discussed further on. Touching the two rocks with the finest depictions of "masks" (Figure 2; E-15) is a medium-sized block (95cm by 200cm) with a horizontal upper surface featuring two parallel quartz veins. Its position (marked 1 in Figure 7), accessibility, and its size and shape (especially the flat upper surface) suggest that it might have been used as a ritual platform. This idea is enhanced by the presence of cupules on its upper surface. However, only in certain light it became obvious that this boulder was marked in a remarkable way. Along the two accessible edges was carved a line of possibly up to eighteen cupules measuring 6cm in average diameter (Figure 14). All cupules are severely weathered. Only seven examples clearly showed up in slanting sunlight, also because the morning dew concentrated in these deeper examples (Figure 15A).

This typical setting of cupules reminded me of the large boulder at Loa’a Site 110, feature BU1, Kaho’olawe Island, Hawai’i (Lee & Stasack 1999: 146-7). There, most of the 32 cultural depressions have been carved likewise along two of its edges. Another interesting quality of feature BU1 will be discussed further on. The importance of the "cascade" as a focal point in the valley is also confirmed by another most interesting rock (marked 2 in Figure 7) that is almost adjoining Rock 1. It is situated at the bottom of the "cascade" and actually lies in the stream itself. It is a large plate of granite (roughly 3 by 6 metres) with a smooth undulating upper surface. Even a conspicuous quartz vein is worn extremely smooth by fluvial action. The rock is sheltered on three sides by large blocks of stone, forming a sort of natural niche, a convenient place for private rituals. One block partially overhangs the plate on its south end. Just west of its open side is another (undecorated) large plate in the pool that is most suitable as viewing platform or gathering place for a small group of people. Stone 2 has a most interesting collection of petroglyphs and, to my knowledge, is the only rock in the whole valley where non-iconic and iconic petroglyphs (including at least one depiction of a "mask" or a "head-dress") are found together with cupules.

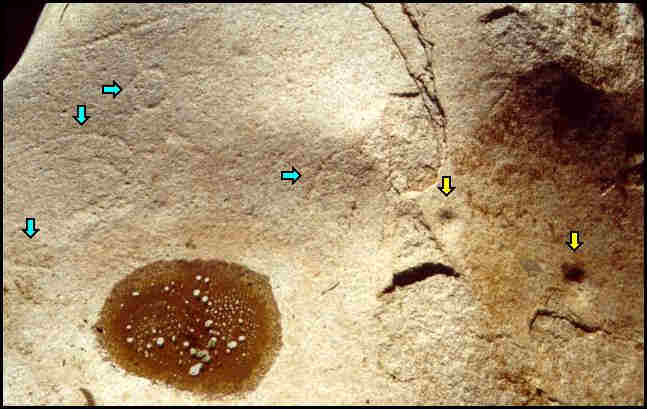

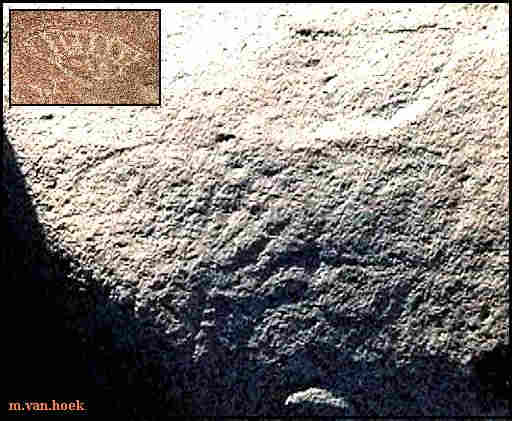

Near its east end and east of a shallow natural basin is a worn ring mark with faint radiating grooves and other extremely faint cultural grooves (Figure 16, blue arrows). South of this group and almost covered by the overhanging block, on a south sloping part, are two worn cupules (Figure 16, yellow arrows).

Near the centre and just east of the most conspicuous quartz vein are at least three shallow cupules in a row (diameters 4, 3 and 10cm). These three cupules (Figure 17, yellow arrows) are severely weathered which may point to great antiquity, but equally, running water during wetter periods may be responsible for the worn character of all the engravings on this stone.

Near its SW end, overlooking the water of the pool, is an interesting collection of ringmarks, some associated with small cupules and radiating grooves (Figure 18 - framed: Figure 17). On the very NW edge of rock 2 is a faint petroglyph of a "mask" or "head-dress" (Figure 19), comparable with other petroglyphs in the area (inset), and some other indecipherable figures. It must be noted that all groups of petroglyphs on rock 2 occupy spaces that are well separated from each other. Perhaps this rock was considered so important because of its location that subsequent cultures decided to add their symbolism only at this rock, respecting the other symbols by using different parts of the rock. Other rocks with cupules and/or "Tacitas" were clearly avoided (possibly out of respect).

The cupule rocks of el Valle del Sol This rock art site is located approximately 24 km to the NE of El Encanto and north of the river Limarí (Figure 1B). Although the rock art in this small gorge (numbered S [Sol]-1 to S-58 in paint on the rocks; again, the numbers are often indecipherable), is not that extensive and sophisticated compared to El Encanto, it is of general importance, also in the scope of this paper. Because of a bottle-neck in the Quebrada Talhuén, erosive forces exposed a large number of boulders and outcrops of different rock types, roughly 70 of which were decorated with mainly non-iconic line-figures such as ringmarks (some with keyhole grooves comparable with the example from El Encanto, Figure 18). Only a few (doubtful) anthropomorphic figures and one possible animal (camelid?) occur (Van Hoek 2000: Fig. 8).

Apart from two outlying decorated rocks near the south end of the gorge, three concentrations of decorated stones may be distinguished: small boulders on the western hill-slopes; much fragmented outcrops on the eastern cliffs (Figure 20) and a remarkable group of cupule rocks very near the stream in the centre of the gorge (Figure 21B). Again, only the cupule rocks will be discussed.

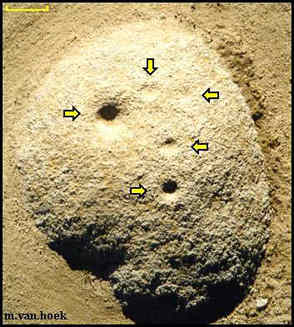

The central group is dominated by a large grey coloured outcrop on the west bank (rocks 1 and 2 in Figure 21B; numbered with paint S-54 to S-56). Rock 1 borders a small pool that possibly is a semi-permanent feature of the gorge. Only six certain cupules (and a few doubtful ones) are found, widely scattered on several horizontal parts of this much fractured and stepped high outcrop (Figure 21C: diameters of cupules stated; drawing not to scale). The only certain cupule on rock 1 is carved very close to the river/pool (Figure 22).

Only the two largest examples of the complex are in a position that would allow "Tacitas" to develop. Touching the outcrop at its west end is a medium-sized boulder (rock 3) with one distinct cupule and another possible one, both rather shallow but recognisable by a lighter (more recent?) patination (Figure 23, black arrows). On the west side is a depression (similarly patinated as the boulder) that also may be a cupule (Figure 23, yellow arrow).

On the other side of the river/pool is a large horizontal, fractured slab (rock 4) with three large cupules (8, 9 and 10cm in diameter), possibly intended to become "Tacitas". About 4m to the north of it is a medium-sized boulder (rock 5) with one shallow cupule (8cm) on its south sloping surface. This cupule has also a lighter patina. One of the striking differences with El Encanto is that "Piedras Tacitas" are almost lacking completely at El Sol. Apart from the doubtful "Tacitas" on rock 4, there are only two rocks with definite "Tacitas" (compare with more than 80 rocks at El Encanto!). One (rock 6) is a large, irregular and much fractured outcrop with three "Tacitas" with a depth and diameter of 12cm on its horizontal upper surface (Figure 24).

Outcrop 6 continues further SW and, under a tree, appears as rock 7 featuring one distinct "Tacita", 13cm in diameter and 14cm in depth. The vertical NW-face of this rock shows a remarkable collection of about eighteen "cupules" averaging only 2cm in diameter and of negligible depth. They were recognised because their light brown colour contrasts clearly against the reddish background. Although they look artificial, they could be impact-marks caused by large pebbles hitting the rock face when the stream was in full force. Their clustering on a reddish part of the rock, however, and their similar dimensions suggest a possible anthropic origin however. On the opposite hill-slope is another group of decorated rocks, three of which are rather small boulders that have cupules as well as very faint traces of other decoration. On the upper undulating surface of rock 8 are two much worn cupules with the same patina as the rock-surface and two faint ovals with a lighter patina. Rock 9 has one distinct cupule (with a clearly differing lighter patina) and one faint circle on its vertical, east-facing surface. On the almost vertical, north-facing surface of rock 10 is one lighter patinated cupule, surrounded by a faintly pecked ring and traces of another ring mark, all most likely added later. This rock rests on a small ledge of grey outcrop rock on the rather steep slope below the main group. Some (or even most) boulders in this group may have been dislocated. Between the two groups is the riverbed covered by sand, pebbles and some boulders. One large irregular and water-worn boulder (rock 11) has four much weathered cupules on its south-facing grey surface, 3, 4, 7 and 8cm in diameter and all rather shallow. Especially the larger ones show a darker patina. To the NW is a flat square boulder (rock 12) with one rather deep cupule of about 7cm in diameter, possibly intended to become a "Tacita".

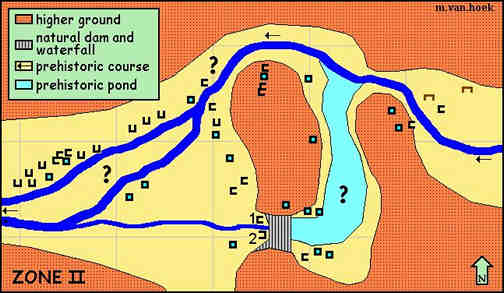

Discussion Archaeological evidence from excavations in the valley makes it acceptable that most of the iconic art dates from the so-called El Molle period (Ampuero 1993). It has also been established that the majority of the iconic art in El Encanto and El Sol and indeed in a large area from Illapell to La Silla (Figure 1B) belongs to the El Molle Culture, which roughly dates from 300 BC to AD 800 (Ballereau & Niemeyer, 1996; Niemeyer & Ballereau 1996). The people belonging to the El Molle Culture probably consisted of small mobile groups of agriculturists and pastoralists that followed the ancient paths of the earlier hunter-gatherers. These earlier groups practised a form of transhumance. In the spring they moved from the coast towards the high ground of the Andes. Some of the river-gorges in the lower foothills were important stopping places on their way up and down the mountains. Importantly, most researchers (Klein 1972: 10; Ampuero 1993: 22; Gallardo Ibánèz 1997: 35) agree on the theory that the "Tacitas" are the oldest cultural manifestations in stone in El Encanto: "Consideramos las Piedras Tacitas o Piedras Morteros como elementos culturales más antigos del lugar" (Klein 1972: 103). For several reasons (grinding food or mixing colours or some unknown ritual) these migrating groups of early hunter-gatherers probably made the first typical basin stones, called "Piedras Tacitas" (Klein 1972; Ampuero 1993). However, Klein also acknowledges the possibility that these "Tacitas" have been used and re-used by subsequent cultures, like the El Molle and Diaguita societies (Ampuero 1993: 22). Yet it is often stated that there is a relation between the "Tacitas" and the petroglyphs of the El Molle Culture (Ampuero 1993: 9). In a directional relationship of symbolic development however, it is better to suggest that the art of the El Molle Culture is associated with the "Tacitas", not the "Tacitas" with the El Molle art. The imagery of the El Molle Culture originated in this valley because of the very special natural qualities of this impressive locus and possibly also because of the presence of the conspicuous "Piedras Tacitas". These basin-stones no doubt will have inspired the newcomers and they decided to execute their own range of petroglyphs on boulders and outcrops near to these "Tacitas". The decision not to place their imagery on these "Piedras Tacitas" was, in my opinion, intentional. Probably they would still have used those "Piedras Tacitas" and possibly one did not want to mix the new and the old functions/symbolism of the place, especially as "Tacitas" may have been used for more practical reasons. Cupule stones may have been ignored, either because most cupule rocks were considered not suitable for their type of petroglyphs (too small, too coarse or too near to the ground level), or because cupules were respected for their antiquity and symbolism. The latter may account for the absence of petroglyphs other than cupules on rock 1, Zone II, El Encanto, although its decorated surface is directly overlooked by several of the finest "masks" of the valley. Although indeed cupules frequently represent the oldest surviving rock art of an area, Robert Bednarik rightly argues however, that often cupules only seemingly represent the oldest rock art motif, simply because they have a good chance to survive, being more deterioration resistant (1996: 126). Unfortunately, up to date there has not been any effort to obtain dating evidence for any of the petroglyphs of El Encanto. Therefore, nothing can be said with certainty about the dating of the cupules and "Tacitas" in this area. Only stylistic characteristics and some rare instances of superimposition of the iconic rock art repertoire give some clues as to a tentative chronology as suggested by Klein (1972). We have noticed however, that many "Piedras Tacitas" also feature cupules (Figure 8) and moreover that cupules often occur solely on small rocks (Figure 12) and on vertical faces (Figure 13). "Tacitas" could therefore have developed after the manufacturers of the cupules acknowledged the special qualities of the place. The presence of cupules (or natural basins) could even have triggered the execution of "Tacitas". If this were true, this would make the cupule the oldest surviving rock art element of these valleys. However, Ampuero (1993) acknowledges the idea that also the rock paintings at El Encanto may represent an artistic expression that could predate the petroglyph tradition of the El Molle Culture. Although only a few rock paintings (mainly in the colour red) survived, there once were possibly many more rock paintings in this valley (Ampuero 1993: 15). In general, mortar stones resulted from the processing of food, fat or ochre or other substances used to make dyes. It is therefore acceptable to suggest that (some of) the "Tacitas" in El Encanto may also have been used to produce the colouring for the rock paintings. In order to provide a reliable chronological framework for the rock art repertoire in the area around Ovalle, it would be most welcome to obtain dates for especially the cupules and the "Tacitas" at El Encanto and El Sol, for instance by way of microerosion analysis (Bednarik 1997), or by micro-excavation techniques (Watchman, Taçon, Fullagar & Head 2000). For that purpose, detailed information especially on the general petrography of the area is needed, as well as geochemical information of the types of patination observed at the several cultural depressions. However, as such scientific analyses involve inspection by specialists, I will have to leave this job to future researchers. However, this survey makes it acceptable that possibly cupules constitute the first elements of rock art around Ovalle after all. Indeed, the cupules at El Sol and especially at El Encanto are mostly extremely weathered and often have the same patination as the rock surface. This may point to great antiquity. However, it must be emphasised here that patina or desert varnish can form quite rapidly in some cases (Lee 1992: 27; Whitley & Annegarn 1994). Also important is the fact that there never appears iconic rock art on any of the stones with cupules or "Tacitas" and that only once (at rock 2 in Zone II) a 'combination' is found of cupules with iconic art (although on separate panels). Also this spatial distinction strongly suggests a chronological distinction between the cupules and de iconic rock art of the El Molle culture. What is almost certain however, is that the siting of the cupule stones (and also of the "Piedras Tacitas") is water-related. It has been noticed earlier in this paper that most of the cupule stones are very near the stream, mainly to the north of it (this spatial preference may relate to the accessibility of the site, which is easier from the north). However, the linear group of "Tacitas" and cupules at Zone II, El Encanto (squares L2 to O1 in Figure 7), seems to form an exception, as many of the stones in this row are 50m distant from the present-day river/pool. This fact, and the linear character of this group brings me to suggest that possibly the course of the river Espinal is nowadays different to the prehistoric course. I already mentioned the jumble of large blocks at the "cascade". Many of these blocks have sharp edges and clearly have been broken a long time after the valley was formed. My initial thought was that the undermining by the erosive forces of a small waterfall caused the collapse of the stone plates, but Klein (1972: 9) suggests that an earthquake was responsible (possibly both factors acted together). Whatever the cause, it is possible that there once existed a prehistoric pond behind (east of) a natural dam and waterfall, and that, at one time, the main course of the river was forced to take another direction. Just possibly the prehistoric stream once ran past the linear group of "Piedras Tacitas" and cupule stones as suggested in Figure 25, which may explain the presence of these cupules and "Tacitas" relatively far from the present-day river. The general distribution of "Tacitas" and cupules in this area seems to support this idea. It is worthwhile to have also this possibility checked in the field by the proposed geological survey.

There is however another strange aspect about the hydrography of the area. Describing Zone II, Klein (1972: 9) does not mention the pool that is so conspicuous nowadays. Instead, he includes photographs of dry ground in front of the "cascade" (1972: Figs 1 and 2). Simultaneously he acknowledges that tectonic forces may have caused irregularities in the course of the river. More importantly, he states (1972: 10) that the stream disappears in the chaos of rocks and follows an underground course that re-appears in Zone I, near the "Gran Peñon". It is therefore safe to suggest that, especially at Zone II, tectonic forces may have repeatedly changed the course of the river Espinal, and this possibly once caused a linear group of petroglyphs to develop along a prehistoric and since long abandoned course of the river. The remarkable absence of "other rock art" in this linear group may imply that the river changed its course again before the El Molle culture arrived in the valley. The presence of water in a suitable geographical place on a path through several different ecological zones from coast to the high Andes not necessarily is the only reason for the execution of cupules at El Encanto. There may have been another, more specific reason for some of the anthropic depressions in the area. There are notably instances, world-wide, where certain rocks, the so called "lithophones" or rock gongs, were noted (and often marked) for their acoustic qualities (Taçon, Fullagar, Ouzman & Mulvaney 1997: 946). It must be emphasised here however, that cultural depressions in lithophones are definitely not the result of casual use. Such cultural hollows are quite intentionally shaped features involving well-targeted percussion. By definition however, such utilitarian percussion-depressions will be regarded neither as true cupules nor as rock art. Sound certainly was important in most prehistoric societies (see the web site of Steven Waller). Throughout southern Africa for instance, there are rocks on which clusters of randomly executed peck marks are found, "not created as things to be seen, but as the residue of certain San rituals at which the production of percussive sound such as hammering or drumming was required" (Ouzman 1998: 38; 2001). Huwiler (1998: 148) discusses the function of several "lithophones" of Zimbabwe, called Mujejeje locally. These granite rocks are still ringed to-date to make contact with the ancestors, which are buried nearby. His book also contains a CD-ROM with no fewer than six recordings of the surprisingly varied sounds produced at one of these "Mujejejes". The enormous rock art site of Twyfelfontein, Namibia, has several rocks with possibly rock art related acoustics and several spots with fine echoes (Twyfelfontein). At Balepetrish, on the northern shore of the island of Tiree, Scotland, I once visited the "Ringing Stone". This is a large boulder that is pitted with large but rather shallow basins, covering almost every surface. When hitting this rock with a pebble that is kept in one of the basins, a bell-like peal is heard. These depressions most likely originated because of the frequent use. In a deep shelter at Bhimbetka, India, there is a boulder (with seven, probably very old cupules) that is supposed to be a rock gong, but this quality is now severely questioned, (Bednarik, Kumar & Tyagi 1991: 34) although these researchers confirm the existence of true "lithophones" in India. I already mentioned BU1, the large boulder on Kaho’olawe Island, Hawai’i, with its typical arrangement of large cultural depressions around its edges, resembling stone 1 at Zone II, El Encanto. Surprisingly BU1 is also special because it resonates with a bell-like peal when tapped (Lee & Stasack 1999: 146). It may now be significant that at least two stones at El Encanto, 1A and 1C in Zone I, are remarkable for having a certain acoustic effect when being (carefully) tapped with a pebble. The acoustic property is only evident at those parts that clearly have been affected by exfoliation, a natural weathering process, characteristic for granite. Although the ongoing exfoliation process may have developed the acoustic effect after the manufacturing of the depressions, it may be significant that the heavily clustering of small cultural depressions is found only on an "acoustic part" of boulder 1A, whereas the single cupule is found isolated on the "silent" top. Also the triangle of depressions on boulder 1C is found on an acoustic part very near ground level, while the upper part of the vertical surface is "mute". It is possible that still other "acoustics" exist in the valley or have been transformed into "Piedras Tacitas". Possibly, ritually produced petro-sounds were an important aspect of prehistoric life at El Encanto. Although Chile abounds in rock art, both iconic and non-iconic, it is surprising to notice how scarce, even rare, cupules are at some major rock art concentrations. For instance, the cliff site at Rosario, Lluta, has no cupules at all, although many rock panels feature natural depressions (some possibly worked on and some definitely incorporated into a design) that may have triggered the creation of the art. Further south, of the more than four hundred petroglyph boulders at Tarapacá 47, only two boulders feature one artificial depression each, too few to speak of a cupule tradition. Therefore, the occurrence of a relatively large number of cupule rocks near Ovalle may be regarded as an exception, especially as other rock art complexes of the El Molle culture seem to be bereft of cupules (Ballereau & Niemeyer, 1996; Niemeyer & Ballereau 1996). For that reason, the possibility that the cupules at El Encanto and El Sol are executed by a different culture than the El Molle and for different reasons must be seriously taken into account. The main target of this survey was to see whether it was justified to consider the cupules in those two valleys as a class of cultural depressions that are distinctly different to the "Tacitas". Indeed, the relatively many new finds of authentic cupules, especially those on small rocks or on vertical surfaces, confirm that the majority of the true cupules in this small part of Chile can no longer be classified as small or unfinished "Tacitas", even when such cupules are larger than average. The relatively large numbers of cupules, together with their specific spatial distribution pattern, make it justifiable to consider this group to be the remains of a modest regional cupule tradition. This survey also made it acceptable that cupules appeared during the initial stages of exploration and occupation by the early hunter-gatherer groups. Therefore, the cupules at El Sol and El Encanto may even pre-date the "Tacitas".

Acknowledgements I would like to thank my wife Elles for her assistance during fieldwork at El Valle del Sol and El Valle de El Encanto in 1999 and 2000. I would like to thank Matthias Strecker for his most useful suggestions. I am also indebted to the curator of the Archaeological Museum of La Serena, Gaston Castillo, who kindly informed us about the rock art at El Valle del Sol.

—Questions, comments? Write to: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com— —¿Preguntas, comentarios? escriba a: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com—

How to quote this paper / Cómo citar este artículo: VAN HOEK, Maarten . Tacitas or cupules? an attempt at distinguishing cultural depressions at two rock art sites near Ovalle, Chile.. En Rupestreweb, https://rupestreweb.tripod.com/tacitas.html 2003

REFERENCES

AMPUERO, B. G., 1993. Arte Rupestre en El Valle de El Encanto. Editoral Museo Arquelógico de La Serena. La Serena. AMPUERO, B. G. & M. RIVERA, 1964. Excavaciones en la Quebrada de El Encanto, Departemento de Ovalle. Arqueológico de Chile Central y Areas Vecinas. Santiago. AMPUERO, B. G. & M. RIVERA, 1971. Las manifestaciones rupestres y arqueológicas del Valle de El Encanto. Publicaciones del Museo Arquelógico de La Serena. Boletin 14. La Serena. BALLEREAU, D. & H. F.NIEMEYER, 1996. Los sitios rupestres de la cuenca alta del Río Illapel (Norte Chico, Chile). Chungara, Volumen 28, 1-2; 319-352. Universidad de Tarapacá, Arica. BEDNARIK , R. G. 1996. Early rock art in the Americas: a contextual study. Survey 9-10-11-12, 1993-1994-1995-1996: 119-131. Pinerolo, Italia. BEDNARIK, R. G. 1997. Microerosion analysis of petroglyphs in Valtellina, Italy. Origini; Preistoria e Protostoria delle Civilta Antiche XXI: 7-22. Italia. BEDNARIK, R. G., G. Kumar & G. S. Tyagi. 1991. Petroglyphs from Central India. Rock Art Research 8 — 1: 33-35. Melbourne. CHACAMA, J. & G. Espinosa. 2001. La Ruta de Tarapacá: Análisis de un mito y una imagen rupestre en el Norte de Chile. Boletín-e AZETA Julio 1999 (http://www.uta.cl/masma/azeta/tarapaca). COSTAS GOBERNA, F. J. & P. NOVOA. 1993. Los grabados rupestres de Galicia. Monografías 6. La Coruña. GALLARDO IBÁÑEZ, F. 1997. El Norte Verde y su prehistoria. La tierra donde el desierto florece. In: Chile Antes de Chile: Prehistoria: 32-43. Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino. Santiago. HUWILER, K. 1998. Zeichen und Felsen. Freemedia, Deutschland. IRRIBAREN, C. J. 1949. Paradero indígena del Estero de Las Peñas. Publicaciones del Museo Arquelógico de La Serena. Boletin 4. La Serena. IRRIBAREN, C. J. 1954. Los petroglifos de la Estancia Zorrilla y Las Peñas en el Departemento de Ovalle y un teoría de vinculación cronológica. Revista Universitaria XXXIX. Santiago. KLEIN, O. 1972. Cultura Ovalle. Complejo Rupestre "Cabezas-Tiara". Petroglifos y pictografias del Valle del Encanto, Provincia de Coquimbo, Chile. Scientia 141, 5-123. Valparaiso. LEE, G. 1992. The rock art of Easter Island; Symbols of Power, Prayers to the Gods. Monumenta Archaeologica 17. Los Angeles, U.S.A. LEE. G. & E. STASACK 1999. Spirit of Place. Petroglyphs of Hawai’i. Los Osos, California. METHFESSEL C. & L. METHFESSEL. 1998. Cúpulas en Rocas de Tarija y Regiones Vecinas. Primera Aproximación. Boletín 12: 36-47. SIARB, La Paz. NIEMEYER, H. F. & D. BALLEREAU, 1996. Los petroglifos del Cerro La Silla, Regíon de Coquimbo. Chungara, Volumen 28, 1-2; 277-317. Universidad de Tarapacá, Arica. OUZMAN, s. 1998. Towards a mindscape of landscape: rock art as expression of world-understanding. In: Chippindale, C & P. S. C. Taçon (eds.) The archaeology of rock art. Cambridge University Press: 30-41. Cambridge. OUZMAN, S. 2001. Seeing is deceiving: rock art and the non-visual. World Archaeology Vol. 33(2): 237-256. Archaeology and Aesthetics. QUEREJAZU LEWIS, R. 1998. Tradiciones de Cúpulas en el Departemento de Cochabamba. Boletín 12: 48-58. SIARB, La Paz. TAÇON, P. S. C., R. FULLAGAR, S. OUZMAN & K. MULVANEY 1997. Cupule engravings from Jinmium-Granilpi (northern Australia) and beyond: exploration of a widespread and enigmatic class of rock markings. Antiquity 71 / 274: 942 — 965. London. England. TILLEY, C. 1994. A phenomenology of landscapes: Places, Paths and Monuments. Berg Publishers. Oxford. VAN HOEK, M. 1997. El arte neolítico en las isles británicas: Un fascinante legado cultural. En: Arte Rupestre Mundial. El mensaje pétreo de nuestros antepasados. Arqueologia sin fronteras. 36-42. Madrid. VAN HOEK, M. 2000. El Valle del Sol. Petroglyphs in the Coquimbo Region, Chile. Adoranten 2000, 69-75. Underslös, Sweden. VAN HOEK, M. 2002a. The Rosario birds - possible indications of El Niño disasters in the Chilean Atacama Desert. Almogaren XXXII-XXXIII / 303-328 / 2001-2002. Wien. VAN HOEK, M. 2002b. Symbiosis in rock art. A rare example in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile. Adoranten 2002, 55-62. Underslös, Sweden. WALLER, S. J. 1997. Rock Art Acoustics: http://www.geocities.com/CapeCanaveral/9461 WATCHMAN, A., P. TAÇON, R. FULLAGAR & L. HEAD. 2000. Minimum ages for pecked rock markings from Jinmium, north western Australia. Archaeol. Oceania 23, 1-10. WHITLEY, D. S. & H. J. ANNEGARN. 1994. Cation-ratio dating of rock engravings from Klipfontein, Northern Cape. In: Dowson, T. A. and J. D. Lewis-Williams (eds.). Contested images: diversity in southern African rock art research. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. [Rupestre/web Inicio] [Artículos] [Zonas] [Noticias] [Vínculos] [Investigadores] [Publique]

Esta

pagina ha sido visitada

|