|

Harry A. Marriner harrymarriner@unete.com

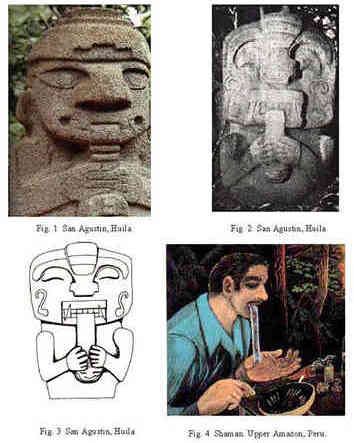

INTRODUCTION: During the Spanish conquest of Colombia, most shamans, and other persons (chiefs or caciques, zipas, zaques, and jeques) that had been indoctrinated into secret societies, were killed before anyone bothered to ask about the meanings of the rock art motifs found in nearly all areas of Colombia. These religious and political leaders were probably the unknown artists who painted or engraved rocks that we find scattered throughout Colombia today. Most likely the jeques or high priests were the painters of the majority of the works we see today. They were the ones who could predict the future, talk to the spirits of dead ancestors, change themselves into animals, go on shamanic flights, control the movement of the sun, bring rain, stop floods, balance the cosmos, and heal the sick. A complex preparation for Muisca priesthood most certainly affected the candidate's perception of the world and the cosmos for the rest of his life. Attempts to interpret Colombian rock art should take this altered perception into consideration. Young boys were selected for priesthood when they were ten years old and isolated in a hut for four to six years. They were only allowed to eat one meal per day consisting of toasted corn, small potatoes and wild herbs. No salt was allowed. Their beverage was a local fermented corn beer called chicha. Candidates were not allowed to leave the hut during daylight hours and were served food through a small hole. After eating, the only parts of the body that could be washed were the fingers. When the candidate finally completed his many years of schooling, he was washed with cold water, dressed in a white manta or cloak, and presented to the chief for consecration. The final test before being ordained was one of sexual abstination. The candidate had to sleep next to two fourteen year old girls for four months and not touch them. If he failed this test he was killed during the early Muisca period. During the later Muisca times the boy who couldn't control himself was simply allowed to return to his former place in society. Successful candidates were ordained as jeques and spent most of their time masticating coca mixed with organic lime during the night near a cave or hut that was isolated, but only a short walking distance from the tribal center. Here they performed their priestly duties and went on vision quests. After returning from their vision quests, initiations, rites, or shamanic trances, the learned ones would record their visions or other information important to them or their tribe, by creating pictographs or petroglyphs at sacred sites that would be there for future reference or mantric use. These were important sites, reused over and over again for ceremonies such as: marriages, initiation, prayers and celestial observation. The Catholic Church insisted that every priest in charge of indoctrinating a tribe interrogate the Indians to find out who were the "mohanes, chupaderos and hechiceros" and what "harm" they did. Every way possible was used to separate the Indians from following their traditional beliefs and ceremonies. When this proved impossible, Spanish priests mounted Christian crosses on top of rocks containing native rock art, held mass at sacred Indian ceremonial sites, and even painted Catholic abbreviations such as "IHS" (Zipacon, Cundinamarca) and religious sayings in Latin such as "Ipse Jubet Mortis Nos" (The same person gives us life and death) (Facatativa, Cundinamarca) (Munoz1:18) on the rock using the same colors and dyes used by the Indians to show the power of the Catholic Church over native religions. Indians who survived the Spanish onslaught obviously weren't the ones entrusted with the secret signs, symbols and cosmic knowledge of their tribe. All the survivors would say was that the paintings and engravings were there long before they were born and that their meaning was unknown to them. The few who had some insight into rock art meanings kept their mouths shut to avoid being tortured or killed for beliefs in the "devil." Studies of the meanings behind rock art motifs in Colombia have been frustrated by the lack of knowledge of even which culture made them since most Indigenous populations and their settlements disappeared rapidly when the Spaniards arrived. Today, for example, we can only say that rock art in the Savanna of Bogota and in the mountainous terrain leading down to the Magdalena River valley is in what we call the historic Muisca and Panche cultural zones. In the Panche zone, the province of Tocaima was decimated from 15,000 taxpaying Indians in 1542 to only 1,300 during a forty year period up until 1582. Close to 800 rock art sites have been identified by Gipri in this limited area, with few clues to identify the artists. Since the few remaining natives lost most of their cultural heritage when they were absorbed into the Spanish culture, it's difficult to prove, using available resources, whether the Muiscas, Panches or a previous culture provided the artists who put their marks on stone in these areas. The situation is similar for most Colombian rock art zones, but migration of customs and beliefs may sometimes be traced if rock art motifs are closely examined and compared to other areas. One example of cultural iconographic migration may be seen in the San Agustin area of southern Colombia where a large number of anthropomorphic stone statues clearly show sharp canine teeth associated with the transformation of shamans into jaguars. This indicates a possible connection to the area-specific Amazonian jungle jaguar cult beliefs. Another clue that may be used to associate this culture with another area is possible portrayal of phlegm coming from the mouth with a head at the end. This "substance" leaving the mouth has been described variously as an "anthropomorphic figure" (Rouillard 36) an "animal" (Fig.1) and related to the action of "licking, sucking, spitting or ritual vomit" (Sotomayor plate 39) (Figs. 2&3). It's interesting to note that shamans located to the south of San Agustin in the Peruvian upper Amazon River guard one aspect of their power as a thick white phlegm (yachay) in their upper stomach. This represents power as knowledge. Part of this phlegm is regurgitated and given to a student shaman to drink, thereby passing on knowledge and power (Fig. 4) (Vitebsky 24). This act appears to be represented in some of the San Agustin statues and may indicate a link to the Peruvian upper Amazon culture.

Stylistic, symbolic, and technical similarities of gold artifacts of birdmen of the Tairona and the Muisca cultures suggests a possible physical and cultural migration from the Caribbean coastal area of the Tairona to the Andean highlands area of the Muisca around 600 AD, possibly via the Magdalena River (Legast 92). Cultural influences from the lowland plains area east of the Muisca territory may have filtered into the highlands since the acuatic jungle anaconda (large snake) myth is seen in the highland Muisca area represented on ceramics with its distinctive black circular markings. Other influences from the west in the Calima (bird-shaped pectorals) and Cauca (crested bird motif) areas show up in some Muisca-made gold artifacts. North American Indian cultures, expressed many abstract ideas pictorially writing on bark, hides and rocks. These ideas were universally understood for centuries from coast to coast. Indians traveling from one tribe to another had no trouble understanding basic universal symbols, although the largest volume of their picture writing probably represented personal and tribal names (Mallery vol 2 pg 584). Colombian rock art appears to use the same symbol in many different areas, but a personal or tribal name doesn't appear to have been used in Colombia in the same manner as in North America. The meaning of many other symbols may have been almost universal throughout the Americas. The intent of this paper is to present some Colombian rock art motifs and suggest possible meanings using ethnographic comparisons. Interpretation of Colombian rock art symbols is very risky and the author doesn't claim to have "the last word" but, desires to present some ideas based on over twenty years studying Colombian rock art and indigenous history. Hopefully the suggestions presented here will provide a basis for future researchers to further explore the meanings behind symbols painted and engraved on rocks at sites sacred to the ancient inhabitants of Colombia. Several thousand years ago indigenous cultures in the northern part of South America shared a complex system of shamanic beliefs with Central American cultures. This area can be defined as a triangle between Costa Rica, the lower Orinoco River and the northwest Amazon region (Reichel-Dolmatoff:80). Many times (but not always) we can obtain ideas from meanings and uses of rock art signs, emblems and symbols in other cultures to lead us to approximate their use and meaning in the current study area. "Signs" were used to commemorate, instruct, indicate direction, or warn of danger or natural resources close by. "Emblems" were tribal, clan, or secret society designs used to identify tribal boundaries, trade routes, or special sites. "Symbols" were used to represent universal concepts or ones only known to a specific tribe, cult, shaman or individual rock artist. The majority of Colombian rock art appears to be in the symbol category. It should be noted that most Colombian pictographs were painted with a red pigment made from cinnabar, ochre, or iron oxide mixed with fat or other substance to form a watery, but glutinous paste. Most pictographs appear to be "finger painted," but Muisca cotton cloaks were known to have been painted with brushes made from sticks fixed to animal fur. Red may have represented blood (menstruation=life=fertility), or a blood relation covenant in a literal sense related to secret societies. This color may have had a special symbolic meaning associated exclusively with priests or chiefs communicating with their gods. Some white, yellow, and black pictographs also occur, but these are a minority. A black pictograph at a high altitude windswept site near Subachoque, Cundinamarca resembles dark storm clouds possibly associated with a site that may have been used to invoke rain from the sky god. Carved and painted rock statues in the San Agustin, Huila area indicate the probability that many (possibly all?) petroglyphs were also painted. In some areas today Indians accent the petroglyph grooves with vegetable pigments (Gelemur pg 19). In the Mataven River region of the Orinoco, Indians continue to retouch ancient petroglyphs occasionally by deepening the grooves and removing the darker patina. Hopefully future researchers use the ideas presented here as the basis for a deeper study into the meaning of Colombian rock art motifs and that more ethnographic information pertaining to Indian rock art in Colombia is found to confirm these suggested interpretations.

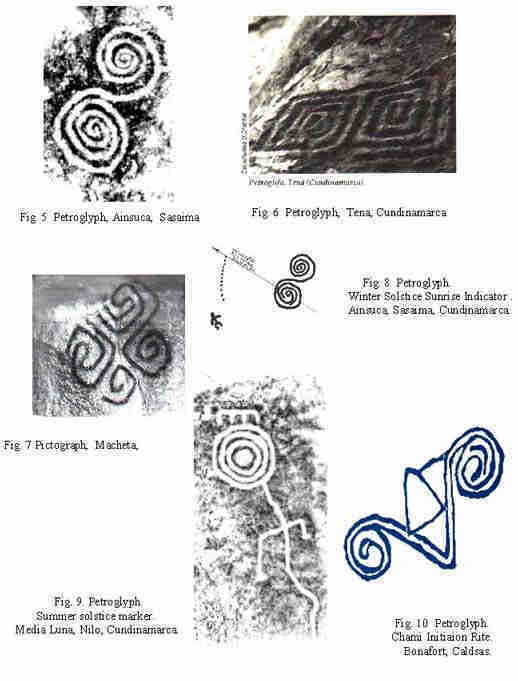

SPIRALS Spirals in rock art are found throughout the world. Many North American Indian cultures associate counterclockwise spirals (starting from the center) with the concept of rising, and the clockwise spiral with the concept of descending. In Colombia, both clockwise and counterclockwise spirals are found in petroglyphs. Most of these are found at altitudes lower than 2,600 meters above sea level. Pictographs of spirals in Colombia are almost always angular. Petroglyphs of spirals are found in both curvilinear and angular styles, but curvilinear spiral petroglyphs are much more common (Figs. 5 & 6). One pictograph in Macheta, Cundinamarca is formed of four angled spirals in the general shape of a diamond (Fig. 7).

Recent archaeological studies indicate that Colombian petroglyphs may have been made during early Carib or Arawak migrations along major river systems such as the Magdalena, Cauca, Amazon and Orinoco. Later, their Carib coastal relations in Colombia and Venezuela settled many Caribbean islands including Hispanola, Dominica and Puerto Rico. While many similar motifs are found in both pictographs and petroglyphs in some inland cultural zone border areas, the basic design structure of pictographs and petroglyphs is completely different. Most petroglyphs are curvilinear while the majority of pictographs are angular. While there are many exceptions, this basic difference strongly indicates an origin from different cultures. Some identical symbols crossed tribal border zones and are found represented in both pictograph and petroglyph form. This is not surprising since women and children were frequently captured from neighboring tribes, and naturally carried their tribal beliefs with them. Petroglyph spirals appear to be related with the summer or winter solstice in some instances. Sometimes a spiral appears to have been used as an indicator for cyclical solar events. This is seen at the Ainsuca site, Sasaima, Cundinamarca where the shadow of a stick placed in the first of a line of small cupules marks the winter solstice sunrise (Marriner 42) by passing through the center of a spiral forming part of a double spiral (Fig. 8). At the Media Luna site, Nilo, Cundinamarca, a shadow also indicates the summer solstice sunrise. Here, the shadow of a rock post begins in the middle of concentric circles, then follows a wavy "tail" of the concentric circles until it meets the ground (Fig. 9). The spiral motif, as well as many variations of circle motifs, was many times used to symbolize the sun at solstice in Colombian rock art. The concept of time being associated with the spiral is not new. It was viewed in the North American Dakota tribe as a snail shell and fully described as being a petroglyph used in the recording and computation of time (Mallery V. 2: 746). The North American Ojibwa used the spiral to record sacred spots or places along a line on a petroglyph story map where a shaman conducted rites during an epic migration (Mallery vol. 2: 566). It's interesting to consider (at least in the northern hemisphere between the equator and the tropic of Cancer), that the clockwise spiral might represent the sun's path from it's rebirth at winter solstice to the zenith passage date. After that date, an observer would face north and see the sun's path as an increasing counterclockwise spiral. The double spiral motif may show an incorporation of both summer and winter solstice symbols in one motif. The winter solstice was considered to be a very special time for shamanic trips making its date very important in the annual calendar of events. Solstices in highland Colombia mark the beginning of the two dry seasons (Dec-Feb and June-Aug). As a hidden or esoteric device, at the same time, these portrayals may have represented a shaman's spirit helper or the shaman himself transformed into an animal capable of bringing back specific knowledge from another spiritual world or balancing the wet and dry periods needed for agricultural production. Oster (1970) listed the counterclockwise spiral as one of the more common phosphenes, or designs seen during a shamanic trance. A similar, but clockwise spiral is drawn by the Tukano Indians of the Amazon basin during a special ceremony (Reichel Dolmatoff, 1978). This may be similar to North American Indian sand painting ceremonies which frequently incorporated spirals to build power or energy (Medicine Hawk 133). In the ancient Samoga (now Bonafort) zone of Caldas, Colombia, Indian chief Merardo Largo of the ancient Umbra cultural zone accompanied University of Caldas researchers in 1995, and may be one of the few living Colombians who has inherited some of the knowledge locked in the engraved stones we are attempting to decipher. Largo views petroglyphs as sacred writing under the protection of a shaman, similar to the stone tablets of Moses containing the ten commandments. Periodically the shaman takes selected tribal members to the rock art site for instruction. In other words, it's a book written on rock, or "hard" knowledge describing a life cycle of birth, baptism, initiation, matrimony and death. He interprets rock art spirals in the following different ways, depending on their location in the grouping, symbols joining them, size, and other subtle differences:

1. THINKING/INHERITED POWER/TRANCE STATE. Merardo interpreted the spiral to be the symbol for a person thinking, but in the same petroglyph group he interprets another spiral as representing inherited power that will be given to a son. If it's true that the Colombian spiral symbolizes "thinking", then it's logical to believe that it could also have been used as a mandala, or a visual device used by a shaman to enter a trance state through prolonged, concentrated staring (thinking) at it at a sacred site at a sacred time of the year.

2. PUBERTY RITE. Chief Largo also interpreted another petroglyph group with two spirals joined with a "V" and a triangular shape in the center, as a site for puberty initiations (Fig. 10). The triangle represents an ax head, associated with males and the capacity to transform and reproduce. The "V" represents union or marriage (possibly a vulva symbol), and the two spirals represent two persons "thinking" about matrimony, but only in the future sense since the puberty initiation rite is a public ceremony announcing that the participant is now ready for marriage. The isolated spiral represents a Tamara, or shaman-priest, in the Escopetera-Pirza (was Samoga) zone who presides over tribal ceremonies. Cupules represent small sauce pans symbolizing a fertile woman.

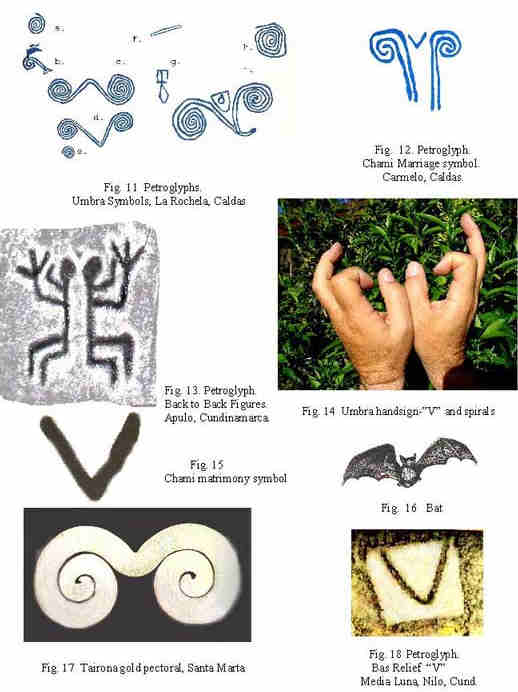

3. MARRIAGE RITE. A third group including spiral petroglyphs at La Rochela, lower Quimbaya area (Fig. 11), was viewed by Largo as an ancient Umbra marriage site. Here, he said, in the early morning, the Tamara or Kurarka (priest) presented the bride to the groom on the flat top of the rock, where the petroglyphs were engraved. Guests sat on the ground, pressed close to the rock, with their backs to the participants. A gully, with a flowing stream, is below the guests. When the sun rose, everyone turned to greet it. When the ceremony was finished, the groom descended and joined the bride. Together they walked down to the stream, and bathed, symbolizing purification. In the center top of the petroglyph grouping is a circle with two parallel lines joined to it (f.). This is the Umbra symbol for the number "12" meaning maude ombea, literally 10 + 2. The petroglyph motif is formed by the "O" meaning "ten" and the two lines meaning "two." This is the only number interpreted so far in Colombian petroglyphs as phonographic writing . It was a reminder that marriages had to take place on the 12th day of the month. The Umbra year consisted of six months. Two of their years (6 months+6 months=12 months) equals one of our modern years. A different date was designated as special for baptisms. A very important and unusual portrayal of an instrument used for astronomical observations is depicted in the middle of the spirals in this grouping (g.). This scientific instrument, made of gold, was used by the Tamara or shaman, as a sighting device to observe the rising sun on the day of the marriage, to confine or limit it's movement, orient its rays, and to make predictions (possibly also to stop the sun's movement south at the winter solstice?). At Carmelo, Piedra del Lomo, in the Quimbaya Media area, there is a rock art site that was used for Chami culture marriages until 1947. It has a petroglyph motif portraying (according to Largo) two participants standing back to back (spirals formed of two lines each) during the marriage ceremony (indicated by a "V")(Fig. 12). Chamis and Umbras have common ancestry and the similarity of designs suggests a common meaning. A petroglyph at Apulo in the Panche zone of two anthropomorphs seated back to back suggests a similar ceremony (Fig. 13). The origin of the Chami matrimonial symbol of two spirals joined by a "V" originates from a hand-sign held over the head during the wedding ceremony. Each participant places their two thumbs together with the last joint containing the thumbnail apart from the other thumb, forming the "V" symbol for matrimony. Both index fingers are closed forming two spirals (Figs. 14 and18). This important discovery is the first confirmation that some Colombian rock art was based on sign language. Note the position of the upraised arms in the previously mentioned Apulo petroglyph . The silhoutte of a "V" formed between the heads, and the curling arms, form a shape similar to the matrimony symbol at the Chami marriage site. The Chami sign language may have been previously based on the shape formed when the participants sit or stand back to back during the marriage ceremony with their arms raised. The only bas relief symbol at the Piedra del Sol petroglyph at Media Luna, Nilo, Cundinamarca is a large "V" indicating that this may be a Panche zone marriage site (Fig. 15). In 1938 Dario Rozo made an attempt to translate Muisca (Chibcha) pictographs based on separating their components, but his efforts were not accepted by the scientific community (Mitologia y Escritura de los Chibchas). Another look should be taken at his works considering recent discoveries.

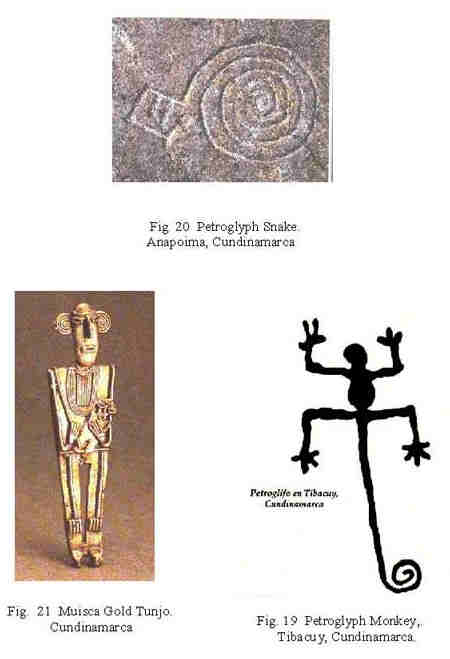

Reichel-Dolmatoff (143) suggests that, in the case of Tairona gold figurines, this "back to back" spiral motif represents the power of fertility, in the sense of growth and vegetal renewal. He also mentions that spirals are decoration details on figurines indicating a shaman in ecstatic flight (thinking or dreaming). It's interesting to note the similarity of the Chami marriage rite hand sign and the Tairona solstice icon pectoral to the shape of a bat in flight. Bats were sacred to the Tairona and many other Colombian cultures (Figs. 16 and 19). SHAMAN-In this same group of marriage-related symbols, the Tamara or shaman is said to be represented at the top right by the largest single spiral, showing that he is different and more important than the others (Fig. 11). He is alone "thinking." The Tamara is the one who guides man, all living things, and nature. He lives alone, celibate at this rock. The role of the shaman in the Desana culture in the Vaupes department is similar to the role of most shamans worldwide. It is to be a societal interpreter and spokesperson for the community before the unknown. The shaman is the intermediary between nature the giver and culture the taker; he is the mediator between the production of food and the consumer, the messenger of the sun and the controller of power that maintains the equilibrium of the jungle world, and the intermediary between the hunter and the owners of nature's productive elements. The shaman doesn't just ask for one animal for one hunter, but negotiates with the "master of the animals" for an abundance of one kind of animal during the hunting season. In return, as payment, he promises to deliver the spirits of humans when they die. (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1986:107, 155-156). PROCREATION OF ANIMALS-The upper left spiral in this grouping is shown to have a "head," and is said to represent the procreation of animals. The glyph below is supposed to represent two animals mating, a fertility symbol (Fig. 11b.). THE MARRIED COUPLE-Below the coupling animals are two double-spiral motifs (Fig. 11c. and d.) opposing each other. The bottom one (Fig. 11a.) begins at the two lines in center of the right spiral. One line represents the man and the other the woman. Note that they are separate at the beginning, but run parallel to each other until the end of their life. The double-spiral above this motif represents the consummated marriage of the couple who live together for life. Another portrayal of the married couple is located at the lower right of the grouping, but with the addition of a triangle with a circle inside (Fig. 11i.). The triangle represents the mother's uterus and the circle represents the child at the moment of birth. It is a prediction of happiness in the near future. Designs of Tairona gold "winged objects" are similar in form to the "married couple" petroglyph and may have a common ancestral origin. Reichel-Dolmatoff (149, 156) (Fig. 17) assigned this motif the name of "Icon D, the solstitial icon" and believes it relates to shamanistic practices involving the sun, procreator and father of all living things. THE CHILD-At the bottom left of the group, a small spiral (Fig. 11e) represents a child, the expected result of matrimony. The spiral at the upper right (Fig. 11h.) represents the everpresent solitary Tamara or shaman.

OTHER ROCK ART SPIRALS Tails of monkeys and coiled snakes are almost certainly portrayed in some Colombian spiral petroglyphs such as those found in Tibacuy, Cundinamarca (Figs. 19 and 20). Muisca gold offerings confirm the importance of animals associated with spirals in tribal cultures (Fig. 21).

In some cultures (for example the Dakota of north America) the spiral represents the shell of a snail or conch, and is related to the recording and computation of time (Mallery 2:746). Time was very important to all shamans. Wind, whirlpools, and whirlwinds are occurrences in nature and should also be considered when attempting an interpretation of Colombian spiral rock art designs. Hopi Indians used the spiral as a symbol of migration to new lands. The Ojibwa used the spiral to indicate physical, sacred places along a line on a pictorial map showing the route of their migration mixing religion and myth. Each sacred site located by a spiral is a place where a shaman held a ceremony or conducted a rite. This migratory path starts from a circle with a dot in the center. The circle represented the world and it's horizon, while the dot represented an imagined island or original home of the human race (Mallery 2:566). It is important to note that a symbol represents a general concept. Interpretation of rock art symbols involve deciphering a meaning that is extended from that general concept. For example, the basic concept of a circle and a dot is held in one place. The dot indicates a fixed spot, while the circle represents holding. In sign language, this symbol is made by encircling arms. Extending this concept by looking at the symbol in context with others on the panel, this symbol may be interpreted to mean many other things such as: waterhole, unable to get out, corralled, out of reach, within, a good place, pinned down, etc. (Martineau 37). Moki Indians of northeastern Arizona say the single spiral is the symbol of Ho-bo-bo, the twister, who shows his power in the whirlwind. Their myth states that a stranger came among the people when a great whirlwind blew all the water and vegetation off the earth. Using a flint he carved spiral symbols on a rock and told them he was the keeper of the breath and that the air which men breathe comes from his mouth. (Fig. 22). The association of the spiral form with wind continues southward. In Mesoamerica a "Wind Jewel" was worn around the neck and hung as a pectoral by priest members of the Quetzalcoatl cult. It was made by cutting a marine conch shell crosswise to reveal the spiral within. The spiral represented Ehecatl (wind), a complex aspect of Quetzalcoatl-Xolotl (venus as morning and evening star). Ehecatl symbolized the air and sky as mediator between the heavens, earth, and underworld, and wind in the form of moving air, be it breeze or wind storm, and on a more esoteric level he represented the breath of life. Ehecatl also set the sun and heavenly bodies in motion (Labbe 15, 17). Further south, in the case of the Muiscas, a "walking spiral" with "feet" at the end of "spikes" protruding from the spiral is frequently seen painted on ceramics (Fig 23). This motif may indirectly represent the sun, but more directly may be a depiction of the marine conch, used as a horn in sacred ceremonies (Fig. 24). The U'wa, genetically related to the Muisca, use conch shells in healing ceremonies and also as musical horns to invite the tribe and the gods to a celebration. The symbolism of the spiral and conch probably also represents lime powder made by grinding conch or large land snail shells, that is mixed with powdered coca leaves for religious purposes. Conch shells, spirals and their representation in rock art obviously are associated with the shaman who uses the coca mixture to communicate with parallel worlds and give tribute to the sun during special ceremonies.

Summary: The spiral in Colombian petroglyphs in many cases, may symbolize a shaman, his activities, or other person, in a trance state, or in heavy, serious concentration during a sacred ritual or ceremony. It probably was also used as a practical device at some sites to indicate the time of a winter or summer solstice ceremony incorporating sunrise shadows. When used to represent an animal such as a serpent, or part of an animal, such as the tail of a monkey, the spiral may have indicated a shamanic spirit helper or the shaman himself transformed into that animal. A variation of the spiral motif with "legs" may also be related to shamanistic healing ceremonies and ceremonial activities involving coca and lime consumption. Associating Colombian spirals with the wind has not been confirmed as in central and northern America, but studies are continuing in this area.

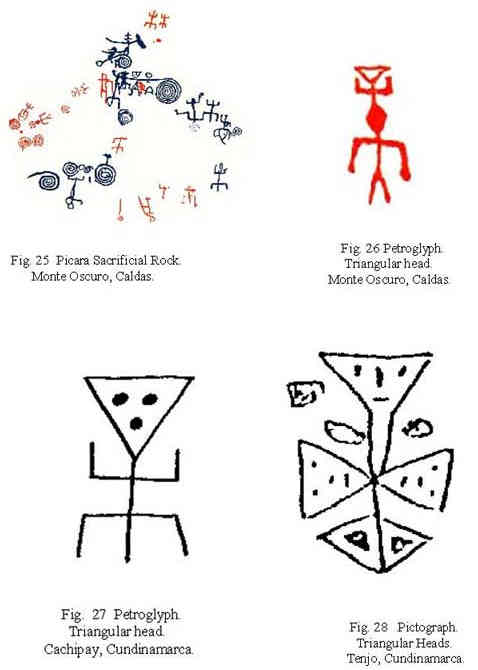

SACRIFICIAL ROCK Chief Largo describes a Picará sacrifice as follows: "The victim, a prisoner, was laid on his back on the rock with his face upwards. The priest, using a polished rock knife, opened the victim's chest and grasped the pulsating heart. This was the way the priest gave homage to deceased brave chiefs. Water was then agitated in large gourds with holes. The noise imitated the sound of the jaguar. The heart was then placed in another gourd and a toast was made to the jaguar god" (Gelemur 94). A petroglyph site located at the base of the Quimbayo or Picara Hill, at Monte Oscuro, in the Escopetera-Pirza Indian Reservation, was described by Gelemur and Rendon (Fig. 25) as a sacrificial site containing petroglyphs engraved by both Picaras and "Chibchas." The term "Chibcha" is actually a term used in modern times by most Colombian anthropologists to describe a language spoken by many different, but linguistically related Colombian cultures (Kogi, Muisca, U'wa, Cuna, and Guane). Gelemur references the high plains Chibchas, who are normally designated by the name Muiscas. She states that "Chibchas" visited and engraved the sacrificial rock using a different style from the Picaras, and used it for fertility rites. In fact, Muisca zone pictographs differ greatly from Picara petroglyphs, and the Monte Oscuro petroglyphs are not considered by this author to have been made by Muiscas. The triangular head (Fig. 26) and other aspects of the sacrificial rock petroglyphs appear to be more similar to petroglyphs found in the Panche cultural zone bordering the Muiscas (e.g. Piedra de Las Cabezas Triangulares (Fig. 27), Cachipay, Cundinamarca). Triangular heads may represent shamanic activity incorporating the weasel or "comedreja" abundant in the Panche/Muisca zone. Weasels were sometimes represented in the form of Muisca gold "tunjo" offerings. An unusual exception is one pictograph of triangular heads at Las Petacas, Tenjo, Cundinamarca in the Muisca zone (Fig. 28) that may represent the three forms (Trinity) of the Muisca god Bochica; or possibly it represents the goddess Bachue and her offspring. She originally populated the Muisca nation through an incestuous relationship with her son.

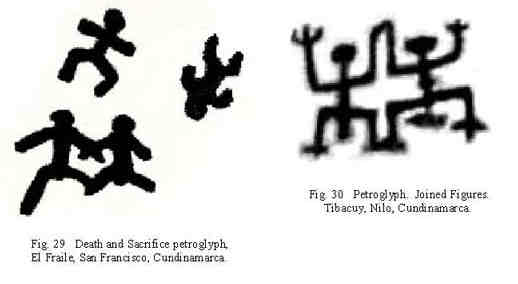

One aspect of the Monte Oscuro site does appear to confirm the thesis that it was a sacrificial site; some anthropomorphic figures are upside down. This method of portraying a dead person or sacrificial victim was common in North American Ojibwa, Chumash, Plains and Iroquis, and in Central American Aztec cultures (Martineau 139; Hudson and Lee 43, Mallery 660) and appears to be a universal concept continued into Colombia. At Piedra del Fraile, San Francisco (Panche zone), Cundinamarca, one anthropomorphic petroglyph figure is portrayed upside down in the midst of many figures engaged in some sort of ceremony (Marriner, Rupestre No. 2:27) (Fig. 29). Ritual death and rebirth is a universal concept associated with the activities of shamans and their initiation rites, so the context of the upside down figure in relation to the entire panel needs to be closely examined in order to determine if the figure represents death in battle, a sacrifice, or a ritual death and rebirth. We also see at Piedra del Fraile two figures with a common foot, that Gelemur suggests in the Picara zone represents a shaman and his sacrificial victim. A Tibacuy zone petroglyph also shows two connected figures (Fig. 30). An additional aid to identification of the Picara site as being sacrificial is the portrayal of two decapitated victims next to one upside down. Their heads are separated from their bodies by the arm of the shaman extended into the form of a spiral. The shaman holds a stone knife. A curved instrument supposedly also used for the sacrifice touches the shaman. (See Fig. 25., Middle of right side).

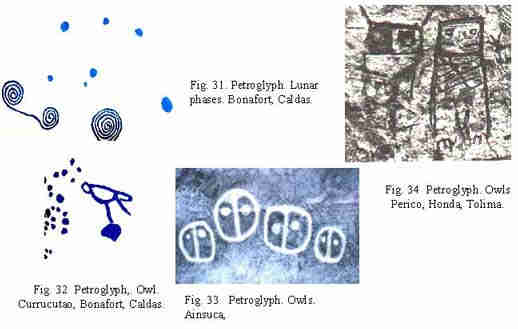

OWL The owl is prominent in both Muisca and Embera-Chami mythology. Gelemur (Gelemur, 125) gives convincing evidence of the portrayal, at a site called La Curva, of an Embera Chami legend about the creation of an owl (Currucutao) from the unfaithful wife of the moon. Cupules at the east side of the petroglyph group supposedly represent the moon (Fig. 31), while an owl is represented on an object supposed to be a nest. These moon symbols may show the full, 1/2 and crescent moon phases (Fig. 32). Two joined spirals may represent the movement of the moon in this grouping. This interpretation is logical since this classical depiction of the spiral symbolizes the orbit of the moon according to Marius Schneider (Cirlot, pg 305). At Ainsuca, Sasaima, Cundinamarca, the owl may have been represented in another way (Fig. 33). This petroglyph is in the Panche cultural zone, bordering the Muiscas who tell the legend of the rebel goddess Huitaca who was turned into an owl by the powerful god Bochica as punishment for flooding the Bogota savanna. A more realistic petroglyph of owls is seen in soft sandstone at Perico, Honda, Cundinamarca (Fig. 34).

In the Amazon area, a Ticuna Indian legend attributes four young owls with lifting a small dim sun to a great height where it was converted into a powerful light. It's possible that the four owls may refer to the helical rising of a stellar constellation. At El Fraile, San Francisco, Cundinamarca a petroglyph of a bird lifting a sun may represent a similar legend (mentioned further in this study) in the Panche/Muisca zone where blackbirds created the first light.

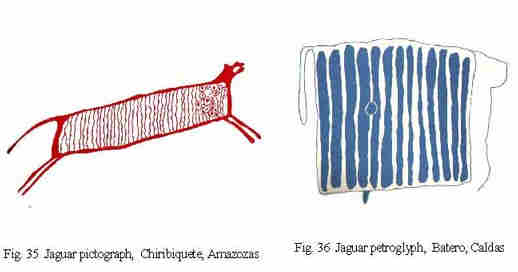

JAGUAR Felines such as the jaguar (felis onca), puma (felis concolor) and tigrillo have been identified in both petroglyphs and pictographs in Colombia. Natives sometimes use the word "tiger" and "jaguar" interchangeably. In Chiribiquete, Amazonas many felines such as jaguars are depicted in red pictographs with vertical lines, horizontal dashes, circles, circles with dots in the center, or squares with dots in the center (Fig. 35). Jaguars are very important to shamans since they are believed to be the only animals who dominate the earth, water and sky, however their primary function is to guard the jungle. Much Amazonian mythology revolves around the jaguar and his creation by the sun to be the sun's principal representative on earth. It is also a symbol of sexual strength and represents the fecundity of the universe. All Amazonian shamans believe they can call and change themselves into jaguars. The Desana and Guahibo use a large dose of snuff to effect this transformation. Others use singing spells, put on jaguar ornaments, teeth and skins for the same purpose. Some shamans believe they are permanently transformed into a jaguar when they die. Chiribiquete representations of the jaguar may symbolize the protective power of the jaguar and its role as regenerator of animal life as well as representing the transformed shaman himself. The jaguar in petroglyph form is found at the Batero, Caldas site as a feline with vertical lines (Fig. 36). The Jaibaná (shaman) in the Embera-Chami culture is very closely associated with the jaguar. They believe that the first men lived inside trees with jaguars who protected the men. After death the shaman is believed to be converted into a mythical being with the body of a man and the head and claws of a jaguar.

An Umbra myth associates the jaguar with the moon. During nights with moonlight a beautiful young woman continuously dreamed of being courted by a special young man. Her friends told her to paint her hands with a black dye. When the young man came and had sexual relations with her during a dark night, her hands streaked his back with the dye. The next morning when everyone left to work, she saw that the man was her brother, so she ran the Cauca River and drown herself. The brother, when he saw he was painted with stripes like a feline, realized what he had done and ran after her. The moon appeared painted after this incident, then disappeared, and the brother was converted into a wolf (Gelemur 132). A careful study of Umbra cosmology may show a relationship between the wolf and a certain star or constellation, and the jaguar and the moon. This jaguar petroglyph could very well have been engraved as a reminder of the Umbra myth as well as indicating a sacred place where a shaman went into a trance to transform himself into a jaguar.

SUN AND MOON A pictograph at Suacha (Sua=sun; Cha=son), Cundinamarca, may represent the Muisca sun god Sua or an important Muisca chief or shaman since Muisca chiefs believed they were the sons of the sun, (Fig. 37a). This shaman or chief costumed as an eagle, vulture or condor may represent something similar to the Mesoamerican concept of a "sun" vulture sending sacrificial offerings to the awaiting sun. Huitoto Indians of the Colombian Amazon wore a headdress resembling the Suacha pictograph for the "pulling of the hairs" puberty ceremony for girls. The moon goddess Chia may be portrayed next to the Suacha sun figure as an anthropomorph with a circle for the head. A dark circle next to a series of vertical lines may represent a lunar cycle at Altania, Subachoque, Cundinamarca (Fig. 38).

Petroglyphs representing the sun are found in varying styles at sites such as: Santandercito, Cundinamarca (Fig.39), Media Luna, Nilo, counterclockwise spiral (starting from the middle)Cundinamarca (Figs. 40, 45 and 46), La Herrada, Quimbaya Baja region of Caldas and Covadonga, Cesar. In places like Covadonga, the ceremonial sun mask may have been represented in rock art. The actual mask uses feathers to represent the rays of the sun (Rupestre 3 pg 23). The Kaggaba Indians of this region are prohibited by tradition to look at the sunrise at certain times of the year. Anyone looking at the sunrise is transformed into a petroglyph. Emblems of J'ui (the sun) engraved on rocks in this area may remind tribal members of this prohibition (Fig. 41). The La Herrada site is said to contain a petroglyph group of the sun in an annual eclipse with the moon next to it (Fig. 42) (Gelemur 151). A depiction of the moon (Jedeko) over the head of a mythological being is supposedly engraved at La Herrada (Fig. 43) and the moon in four different phases as mentioned previously at Currucutao, Caldas (Fig. 31) (Gelemur 151, 163, and 125). At Sachica, Boyaca the sun may have been depicted in pictograph form as three concentric circles alone or with spiked rays. A painted Muisca cloth from Belen, Boyaca shows the sun as two concentric circles with spiked rays (Fig. 37b). In many cultures, portrayal of a head with emanating rays (head of the sun) has been confirmed to represent a spirit or a man "enlightened" from on high, such as a shaman with special knowledge (Mallery 2:474). Contemporary Yagua shamans of the Colombian Amazon draw the moon as a shaded-in circle while the sun is represented as a shaded-in circle with short lines extending outward (Fig. 44).

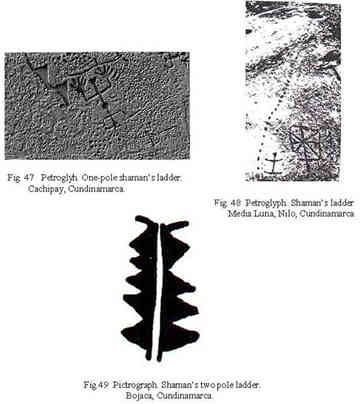

SHAMAN'S LADDERS Many native cultures believe that the first men were able to communicate with the celestial world and it's inhabitants by climbing a ladder to the sky. Various myths describe how angered gods destroyed this ladder. Privileged shamans in trance state communicate with the upper world by being carried by bird spirit helpers or themselves being transformed into birds. At other times they climb trees, or notched single or double log ladders to the sky world. Some shamans shoot arrows into the sky to form ladders to allow a dead person's trapped soul to travel from the sun to join dead kinfolk in the underworld (Vitebsky 17). These different types of ladders may have been portrayed in rock art at the following sites in Colombia: Cachipay (Fig. 47), Suacha (Fig. 38), Media Luna (Fig. 48), and Bojacá (Fig. 49).

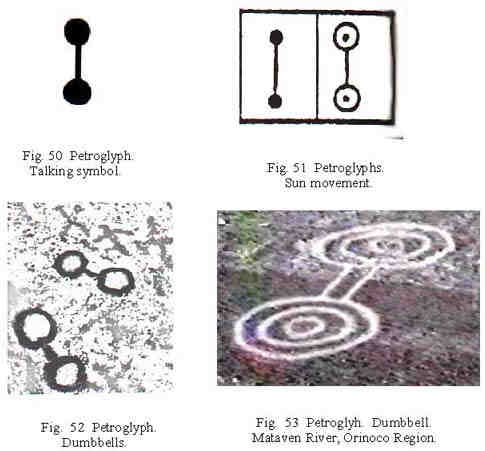

PARALLEL WORLDS AND EMERGENCE Nearly all religions believe in parallel words. The number of worlds and the location of the home of gods and souls of the dead varies with each culture, but generally there is one world (the earth) where humans live, one world (sky) where the gods live, and one world (underworld) where the dead live. Tribal origin myths may also include the concept of "emergence" from one world to other. One common element in all of these cultures and religions is "communication between worlds." This communication may be symbolized as a ladder as mentioned above, a spiral or a dumbbell shape. DUMBBELL: The dumbbell or barbell motif is seen frequently in the southwest USA and south into Mexico, where it has been interpreted as speech (a line) between two persons (2 circles) or as a symbol pointing to hidden rock art panels (Fig. 50), and also as the sun moving from solstice to solstice (Fig. 51). In Colombia this motif is encountered as a petroglyph in places such as El Fraile, San Francisco (Fig. 52), and at the Mataven River, Orinoco (Fig. 53). This symbol may represent any of a variety of ideas relating to communication or movement from one place to another, such as: two people talking, a shaman moving from one world to another, the sun moving from one solstice to another; or a road from one village to another. The general idea, however, is communication via thought, speech or movement from one place to another. It may represent the shaman visiting a parallel world in some cases.

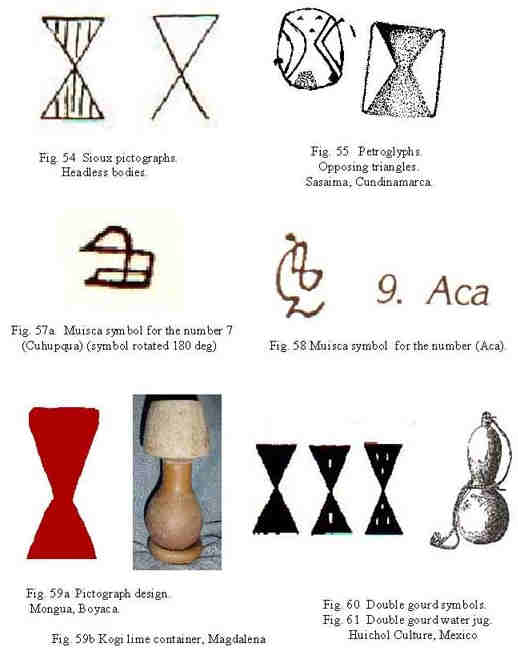

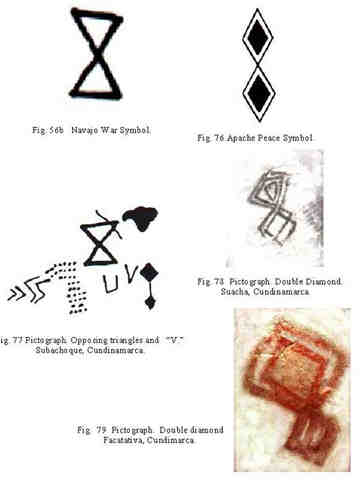

SPIRAL: We have suggested some possible interpretations for the spiral earlier in this paper. The spiral is used in southwest USA at times to symbolize the emergence of man onto the earth from another parallel world. In Colombia the spiral appears to be more closely related to shamanic trance-induced journeys. When there is only one spiral motif on a rock, it may indicate a direction (up or down) to be taken to find water, or an important site nearby. A indicates "going up" like an eagle or condor gaining altitude, while a clockwise spiral indicates descent or going down (Martineau 19). At sites associated with shamanic trance journeys, the direction of the spiral might indicate whether he was travelling to the sky world or into the underworld. OPPOSING TRIANGLES: Muisca pictograph and petroglyph sites occasionally include a motif composed of two opposing triangles, apex to apex (Figs. 57, 58, 59a, 60). Sometimes these figures include two eyes and a mouth, making it logical to assume they are anthropomorphic figures (Fig. 55). Similar North American Indian pictographs have been interpreted by native speakers as "headless bodies."(Fig. 54) In Colombia they are more like "bodiless heads." Some options for interpretation include: 1. A shaman visiting the sky world and the underworld. 2. The male and female aspects. 3. The sky god above and the earth god below. 4. Father sun and mother earth. 5. A couple mating. This interpretation stems from the concept of the sun's rays (male) fertilizing the earth (female). Another way this concept may be symbolized is merging two triangles to form a six-pointed "star of David" as seen in Canica Baja, Subachoque, Cundinamarca (Fig. 56a). A six-pointed star was found on a sun disk in Yucatan. This symbol represented the rays of the sun to the Maya and Aztec cultures. 6. A stellar constellation, possibly Pisces. 8. Aca, the number 9. In the Muisca Chibcha language, the number 9 is formed using opposing triangles representing a frog whose tail is beginning to form another tail. It is also the symbol of the moon. Croaking frogs announce the coming of rain to the Muiscas and signal the time to begin planting crops.(Fig. 58). 9. A symbol of war. Opposing arrowheads in North American rock art many times represent war. The association of this motif with faces in Colombia weakens support for this interpretation, but doesn't discount it entirely. 8. Symbol for the double gourd lime container (poporo).( Fig. 59b.)This container is used by the Kogi Indians of the Sierra Nevada, Magdalena region to store lime made from ground marine conch shells. Lime is used in conjunction with coca chewing (mambeando). Sexual and mythological associations have been described by investigators of the Kogi culture. Mexican Huichol Indians use the same symbol for a double water gourd (Fig. 60). The gourd is used by the hikuli (peyote) seekers on their journey as drinking vessels, as well as to hold the sacred water they take home with them (Fig. 61).

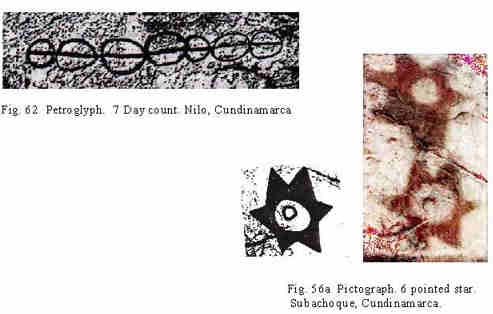

CONCEPT OF TIME: In pictographs, at Altania Alta, Subachoque, 27 vertical lines next to a dark circle, may be day markers counting the number of days the moon is visible in one lunar cycle (Fig. 38). As petroglyphs, at Media Luna, Nilo, one horizontal line of seven circles joined by one horizontal line across the diameters, may symbolize a seven day lunar phase (Fig. 62).

ANIMALS: Portrayals of animals are found in both pictographs and petroglyphs in Colombia. A few of the many animals depicted in Colombia follow: Birds are realistically portrayed in many areas such as the Orinoco where long beaked petroglyphs resemble the North American Thunderbird (Figs. 63 and 64). At the Pacific Ocean island of Gorgona there is one petroglyph of a crested bird (Fig. 65). In the Panche area of San Francisco, Cundinamarca we find a bird rising from a circle with a dot in the center. The bird glyph of San Francisco (Fig. 66) may represent not Muisca cultural spillage over the border in the form of a bird bringing the first light to humans. Chiminigagua was the god who first gave light to the earth by sending many large black birds to all points of the sky breathing light into the primeval darkness. Birds associated with spirals at the Piedra del Sacrificio mentioned above probably represent spirit or protector animals of a particular shaman.

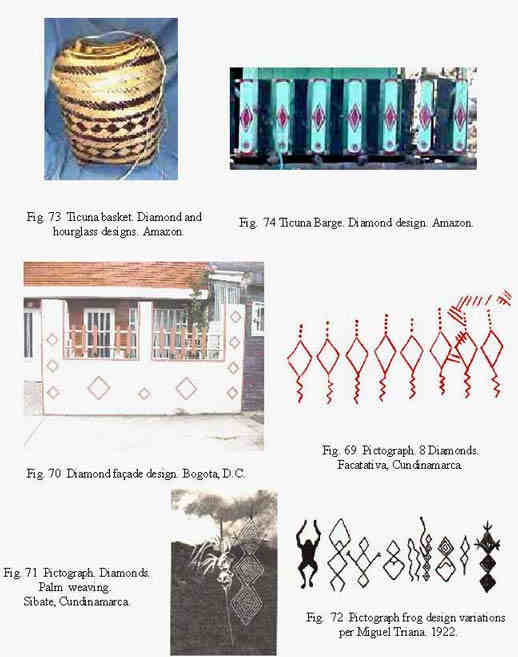

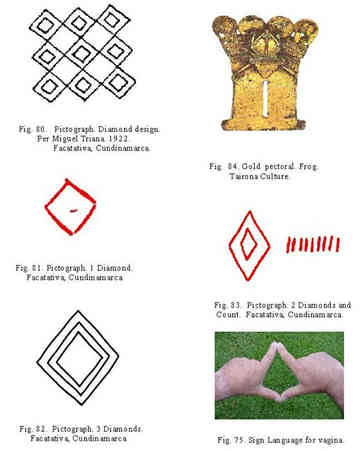

Frogs or toads are believed by many Colombian anthropologists to have been depicted symbolically as red diamond shape pictographs in the Muisca area (Figs 80-83). A few are realistically portrayed as petroglyphs (Figs. 67, 68). This rhomboid may represent the distinctive wide body shape of the Bufonidae frog or the Atelopus with its sharply pointed nose. Realistic gold frog votive artifacts of the venomous Atelopus and wide-bodied Bufonidae have been found in the Muisca zone indicating a sacred interest in this animal. Cochranella frogs (both terrestrial and amphibious stages) have been found engraved on stone matrices used to make beaten gold adornments, and Centrolenido frogs are seen as Muisca ceramic bowl decorations, especially the large species Centrolene Geckoideum. Frogs in some Chibcha language family groups (Kogi and Muisca) are feminine, and are closely associated with lakes and rain. This association of frogs and water is still seen today in the Colombian capital. The frog symbol is the official symbol of the Bogota Water Company (Acueducto de Bogota) and is seen on the metal lid covering the water meter at every house. The Kogi believe small black frogs are daughters of the lakes. When these frogs begin to call for water, the tribe must sing to the mother of the rain to bring showers. The beginning of the rainy season is said to be announced by croaking frogs. The author has personally heard the first seasonal croaking of the small green Bogota savanna frog anticipating the first rainfall of the wet season by twelve hours. A Kogi origin myth relates that the Sun's first woman was a toad who was banished for being unfaithful. The Bufo Marinus is a generic frog symbol for that area and continues today to represent a negative, dangerous aspect of the femenine sex to the Kogi.

Fertility, prosperity and crop abundance are also associated with frogs by country folk living in the Muisca territory today. Diamond shaped symbols were, and still are painted to bring rain, good luck and abundant crops. Today these symbols are painted on house fronts just as their ancestors painted them on rock faces (Figs. 69 and 70). There is some indication that pictograph portrayals of frogs in different positions may symbolize different moon phases (Barradas 1941:53). Palm fronds woven into a single or double diamond shapes are placed in planted fields in Muisca territory on Palm Sunday to protect crops, calm storms and even to ease the pain of childbirth (Fig. 71). One diamond placed on top of another diamond is the origin of the Chibcha word aca (meaning number 9) and represents the wet season symbolized by one frog on top of another. The wet season is when frogs reproduce and is also the time to plant crops. The symbol for Cujupcua, the number 7, is somewhat similar to the symbol for number 9. Cujupcua symbolizes two ears or two basket handles associated with a harvest. Variations of this symbol only the ruling class was allowed to eat deer meat. Rabbits, curi and birds were may have been painted as pictographs at Suacha, Facatativa and Subachoque, Cundinamarca (Figs. 57a., b., c.). Miguel Triana, a pioneer Colombian rock art investigator, believed that most diamond shapes were frog depictions (Fig. 72). Ticuna Indians of the Amazon paint the diamond shape on wooden buildings for good luck and also as a basket decoration, but their literal translation of the symbol is a vulva (Figs. 73 and 74). Kogis associate the open mouth of a frog with the vulva. In modern day handsign language the word "vagina" is signed by touching the right index finger to the left index finger and the right thumb to the right thumb (Fig. 75). A diamond within a diamond may indicate pregnancy and the associated nine lines on one pictograph (Fig. 83) may indicate a nine month gestation period.

Interpretations mentioned above differ from the North American Indian meaning of the diamond symbol which means peace. The distribution and context of the North American symbols for war (two triangles joined apex to apex)(Fig. 56b) and peace (diamond shape)(Fig. 76) in Muisca territory should be closely studied before completely eliminating this possible interpretation, since both motifs are found frequently and were obviously very important to the culture who painted them. Note the similarity of Figure 56b to 77, and the similarity of Figure 76 to Figures 78 and 79.

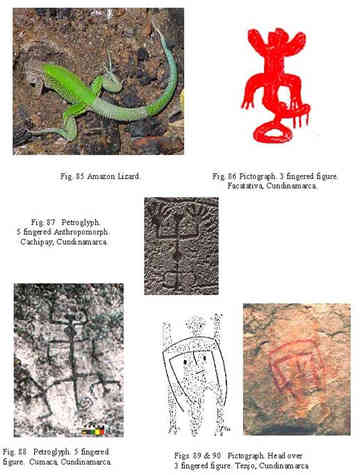

A gold Tairona pectoral with spirals and a frog on an anthropomorphic figure may represent a shaman's spirit helper and aid in interpretation of rock art in that area (Fig. 84). Lizards are difficult to separate from humans and acuatic frogs with tails in Colombian rock art petroglyphs. A shaman with raised arms is easily confused with a lizard or an acuatic frog with extended legs. One clue to identification is the number of fingers on the figure and the representation of a tail or penis (Figs. 85, 86, 87 and 88). Usually the petroglyph form has three toes or fingers, but other times no fingers or toes are shown. In Tenjo, Cundinamarca, a rare two color pictograph of a red head over a yellow-orge lizard may indicate that the artist was attempting to show a shaman transformed into an animal (Figs. 89 and 90). Five fingered figures more obviously indicate the intention to depict a human or a simian (Fig. 87). Lizards and frogs, in the Muisca culture, may have been spirit helpers or messengers for shamans, able to enter holes in the earth and rocks and descend to bring back answers to the shamans' prayers to underworld gods. Vaupes Indians believed a small tree lizard (Plica plica L.) represented the Master of the Animals and was assigned a very special phallic symbolism since this lizard has a forked, anchor-shaped hemipenis, which facilitates prolonged coitus. In this context the lizard symbolizes the generative forces of nature. Tairona gold objects and Kogi Indian dancers wear these anchor-shaped Tairona pendants during a dance honoring this lizard. The "spread-eagled" lizard is a common petroglyph found in many zones of Colombia. The anchor shape is found as a petroglyph in Aipe, Huila (insert Aipe rock anchor).

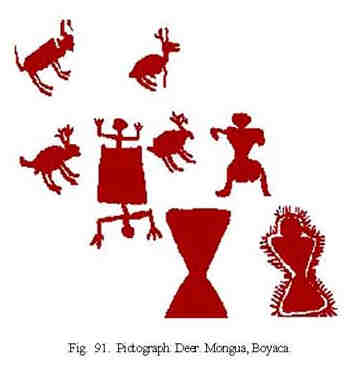

Deer (Odocoileus virginianus and Mazama sp.) were abundant in the Muisca territory when the Spanish arrived. This is probably because of a conservation law in effect at that time;on the protected list. A very rare realistic red pictograph of a hunter possibly holding an atlatl, deer and possibly a shaman in a hallucinogenic trip to the land of the master of the animals to ask for abundant game, is seen at a site in Mongua, Boyaca (Fig. 91). Representations of deer on gold votive objects are also scarce, even though deer meat and bones were very important to the Muiscas. Bones were used to make tools for weaving and working hides. Hides were used as doors to the chiefs' huts. When Muiscas died, their souls went to the cold paramo region or turned into bears or deer. Kogi myths associate the deer to the history of coca. The Tunebo, another Chibcha speaking tribe, believe that when a deer dies, its soul goes into the hills and changes into a human. One gold atlatl with a deer on it suggests that the atlatl was used as a weapon to hunt this animal.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION Interpretation of Colombian motifs at the 100% confidence level is impossible, but by looking at each rock art panel, studying the context of one motif with another, and using meanings from other indigenous cultures, it is possible to reach some tentative conclusions. Suggested meanings included in this paper were based on interpretations from Colombian and other Mesoamerican native cultures and the interpretation of contemporary tribal chiefs who may have inherited knowledge passed down from their ancestors . Hopefully the interpretations here, based on the accumulation of over twenty years of studying Colombian rock art in conjunction with the collaboration of other GipriI rock art investigators will provide the basis for further investigation into the original meaning of pictographs and petroglyphs found in nearly every department in Colombia.

—¿Preguntas, comentarios? escriba a: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com— Cómo citar este artículo: Marriner, Harry A.. Colombian rock art motifs: some ideas for interpretation. En Rupestre/web, https://rupestreweb.tripod.com/motif.html 2002

LIST OF REFERENCES CITED AND SUGGESTED FURTHER READING

Aveni, Anthony F. 1980. Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico. University of Texas Press. Austin. Botiva Contreras, Alvaro. 2000. Arte Rupestre en Cundinamarca. Gobernación de Cundinamarca. Bogota. Castano-Uribe, Carlos. 1998. Chiribiquete: La Peregrinacion de los Jaguares. Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. Bogota. Cates Jr., John M. 1974. El Dorado: The Gold of Ancient Colombia. The Center For Inter-American Relations. New York. Cirlot, J.E. 1983. A Dictionary of Symbols. Philosophical Library. New York. Conway, Thor and Julie. 1990. Spirits On Stone: The Agawa Pictographs. Heritage Discoveries. San Luis Obispo. Dubelaar, Cornelius N. 1986. The Petroglyphs in the Guianas and Adjacent Areas of Brazil and Venezuela: An Inventory. Institute of Archaeology. Los Angeles. Gelemur de Rendon, Anielka and Guillermo Rendon Garcia. 1998. Samoga: Enigma y Desciframiento. Centro Editorial Universidad de Caldas. Manizales. Halifax, Joan. 1982. Shaman: The Wounded Healer. Thames and Hudson Ltd. London. Hudson, Travis and Ernest Underhay. 1978. Crystals in the Sky: An Intellectual Odyssey Involving Chumash Astronomy, Cosmology and Rock Art. Ballena Press. Socorro. Hudson, Travis and Georgia Lee. 1984. Function and Symbolism in Chumash Rock Art. In Journal of New World Archaeology 6(3). Iriarte, Alfredo. 1992. Mitos Muiscas. Amazonas Editores. Bogota. Labbe, Armand J. 1992. Religion, Art, And Iconography: Man And Cosmos In Prehispanic Mesoamerica. Bowers Museum Foundation. Santa Ana. Lloreda, Diana. 1992. Los Muiscas: Pasos Perdidos. Editorial Nomos. Bogota. 1992. Mallery, Garrick. 1972. Picture-Writing of the American Indians. Vols 1 & 2. Dover Publications, Inc. New York. Marriner, Harry Andrew. 1998. Rock Artists and Skywatchers in Ancient Colombia. Privately Published. Bogota. Martineau, LaVan. 1987. The Rocks Begin to Speak. KC Publications. Las Vegas. Medicine Hawk and Grey Cat. 1990. American Indian Ceremonies. Inner Light Publications. New Brunswick. Moore, Hyatt. 1991. The Alphabet Makers. Summer Institute of Linguistics. Huntington Beach. Munoz C., Guillermo. 1995. Rupestre: Arte Rupestre en Colombia. Año 1, Numero 1. GIPRI. Bogota. Munoz C., Guillermo. 1998. Rupestre: Arte Rupestre en Colombia. Año 2, Numero 2. GIPRI. Bogota. 1998. Munoz C., Guillermo. 2000. Rupestre: Arte Rupestre en Colombia. Año 3, Numero 3. GIPRI. Bogota. Patterson, Alex. 1992. A Field Guide to Rock Art Symbols of the Greater Southwest. Johnson Books. Boulder. Perez de Barradas, Jose. 1941. El Arte Rupestre En Colombia. Instituto Bernardin De Sahagun. Serie A-No. 1. Madrid. Preuss, K. Th. 1974. Arte Monumental Prehistorico. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogota. Purce, Jill. 1987. The Mystic Spiral: Journey of the Soul. Thames and Hudson, Inc. New York. Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. 1988. Goldwork and Shamanism. Compania Litografica Nacional S.A.-Editorial Colina. Medellin. Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. 1986. Los Tukanos. Bogota. Rouillard, Patrick. 1987. San Agustin. Editorial Colina. Medellin. Schultes, Richard Evans and Albert Hofmann. 1979. Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers. Healing Arts Press. Rochester. Sotomayor, Maria Lucia and Maria Victoria Uribe. 1987. Estatuaria Del Macizo Colombiano. Imprenta Nacional de Colombia. Bogota. Tompkins, William. 1929. Universal Indian Sign Language. Frye and Smith. San Diego. Triana, Miguel. 1922. La Civilizacion Chibcha. Escuela Tipografia Salesiana. Bogota. Vitebsky, Piers. 1995. The Shaman. Little, Brown and Company. Boston. Ward, J.S.M. 1969. Secret Sign Languages: The Sign Language of the Mysteries. Land's End Press. New York.

ILLUSTRATIONS AND PHOTOS

Figure 1. Preuss foto No. 21. Figure 2. Sotomayor Plate No. 4. Figure 3. Sotomayor Plate No. 39. Figure 4. Vitebsky page 24. Figure 5. Foto by author. Figure 6. Gipri Rupestre 3:79. Figure 7. Botiva page 81. Figure 8. Foto by author. Figure 9. Foto by author. Figure 10. Gelemur page 57. Figure 11. Gelemur page 66. Figure 12. Gelemur page 85. Figure 13. Botiva page 195. Figure 14. Gelemur page 75. Figure 15. Gelemur page 75. Figure 16. The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia (1899) page 472. Figure 17. Cates page 126. Figure 18. Foto by author. Figure 19. Diego Martínez C. Rupestre 1:36. Figure 20. Botiva . Figure 21. Mitos Muiscas page 19. Figure 22. Mallery Vol. 2, page 604. Figure 23. Foto by author. Muisca ceramic "mucura" water jug. Figure 24. Foto by author. Caribbean marine conch shell. Figure 25. Gelemur page 95. Figure 26. Gelemur page 95. Figure 27. Drawing by author. Figure 28. Drawing by author. Figure 29. Drawing by author. Figure 30. Gipri archives, Bogota. Figure 31. Gelemur page 125. Figure 32. Gelemur page 125. Figure 33. Foto by author. Figure 34. Gipri archives, Bogota. Figure 35. Castano-Uribe page 47, figure 8. Figure 36. Gelemur page 133. Figure 37. Gipri archives, Bogota. Figure 38. Drawing by author. Figure 39. Diego Martínez C. archives, Bogota. Figure 40. Foto by author. Figure 41. Gipri archives, Bogota. Figure 42. Gelemur page 151. Figure 43. Gelemur page 163. Figure 44. Vitebsky page 16. Figure 45. Foto by author. Figure 46. Foto by author. Figure 47. Diego Martínez C. archives, Bogota.. Figure 48. Foto by author. Figure 49. Drawing by author. Figure 50. Martineau page 28. Figure 51. Patterson page 86. Figure 52. Foto by author. Figure 53. Foto by author. Figure 54. Tompkins page 72. Figure 55. Gipri archives, Bogota. Figure 56. Foto and drawing by author. Figure 57. Duquesne in Lloreda page 49. Figure 58. Duquesne in Lloreda page 49. Figure 59a. Gipri archives, Bogota. Figure 59b. Foto by author. Figure 60. Patterson page 206.

Figure 61. Patterson page 207. Figure 62. Foto by author. Figure 63. Foto by author. Figure 64. Drawing by author. Figure 65. Gipri archives, Bogota. Figure 66. Drawing by author. Figure 67. Foto by author. Figure 68. Diego Martínez C. files, Bogota. Figure 69. Drawing by author. Figure 70. Foto by author. Barrio San Marcos, Bogota. Figure 71. Gipri archives, Bogota. Figure 72. Triana page 212. Figure 73. Foto by author. Figure 74. Foto by author. Amatura, Amazon River, Colombia. Figure 75. Foto by author. Figure 76. Martineau page 4. Figure 77. Drawing by author. Figure 78. Gipri archives, Bogota. Figure 79. Foto by author. Figure 80. Triana page 188. Figure 81. Drawing by author. Figure 82. Drawing by author. Figure 83. Drawing by author. Figure 84. Reichel-Dolmatoff page 143. Figure 85. Foto by author. Figure 86. Drawing by author. Figure 87. Diego Martínez C. archives. Figure 88. Gipri archives, Bogota. Figure 89. Drawing by author. Figure 90. Foto by author. Figure 91 Diego Martínez C. archives, Bogota.

[Rupestre/web Inicio] [Artículos] [Noticias] [Zonas] [Vínculos] [Publique]

|

Colombian

rock art motifs: some ideas for interpretation

Colombian

rock art motifs: some ideas for interpretation