|

Dart-thrower use in Colombia and its representation in colombian rock art. Harry A. Marriner Investigador independiente de arte rupestre colombiano. Correo electrónico: harrymarriner@unete.com

Spear or dart-throwers (atlatls in Mexico) have been used world-wide since Paleolithic times to throw sharpened wooden darts to kill game animals and enemies. The wooden weapon in essence increases the length of the thrower’s arm and gives a greater initial thrust to the dart. Since distance is limited by the force of one’s arm, the bow and arrow replaced the dart-thrower as the weapon of choice as soon as it was discovered by tribal societies. In certain areas, rock art has been dated using knowledge of when the bow and arrow was first used and depicted in that specific area. Dart-throwers, known in Spanish as Propulsores, Tiraderas, or Estolicas, were called Queskes, Quisques, or Ckechkes, by the Muisca Indians of the Colombian highland savannah in the Cundinamarca-Boyaca area of Colombia. Muiscas (A.D. 700-1600) used the Queske as their primary weapon, not the bow and arrow. A bow with arrows along with a shrunken? trophy head and a club are seen on flat gold and copper alloy Muisca tunjo figures (fig. 1). Arms such as darts, estolicas, axes, clubs, spears, bows and arrows and quivers were frequently represented on tunjos (Plazas: 85). Masses of Muisca warriors using dart-throwers and darts with fire-hardened tips battled Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada during the Spanish Conquest of Colombia in 1538. Selection of this weapon for serious battle was not ideal for professional Guecha warriors since thin shields provided easy defense from the darts. Estolicas were used frequently by the common person and inter-tribal traders. Heavy Macana or Palma Boba wood was used to make Muisca dart-throwers that measured 42-60 cms. long. Darts measuring approximately 1.6 meters long were made from bamboo (Caña Brava or Carrizo). (Castellanos in Rojas de Perdomo: 148)). Removable hardwood dart tips were serrated with jagged cuts. Usually no poison was added to the tips. Two hooks made of bone, stone, or shell faced each other at opposing ends of the thrower (fig. 2) and were fixed into place with Fique or Agave twine covered with tar or tree resin (fig. 3).

This “Andean type” is the style that was most commonly used by Muisca Indians around Bogota and the Guane to the north of them in the state of Santander (Uhle: 111, Tafel IV: 5-7). Ceremonial and miniature estolicas were made from gold and used as burial offerings (fig. 4). Full size wooden estolicas were buried with important mummified persons to protect them in the afterlife (fig. 5) (Marriner: 1). Some dart-throwers were represented on tunjo figures buried as prayers asking favors from Muisca gods (figs. 6 & 7).

Representations and actual dart-throwers (fig. 8) have been found in the high Pisba Paramo and Mesa de Los Santos (see map below), Guane region of the state of Santander at altitudes up to 3,500 meters above sea level (Bruechert: 1) (figs. 156-158. Bray:138 from Schottelius: 213-225) (Cardale de Schrimpff 1987: 5) (Ardila Diaz:188), but the average habitation site of the savannah highlands north of Bogota was closer to 2,600 meters. Unfortunately, no rock art representation of a dart-thrower has been found in the Muisca or Guane cultural zones. Other tribes in Colombia also used the estolica as a weapon. Panches, bordering the Muiscas, were recorded in historic times by the Spanish conquistadors used “darts” (Simon: 3, 283) as well as the bow and poisoned arrows (Castellanos: I, 122). The Tairona culture had also progressed to the use of bow and arrows by the time of the Conquest as seen on a gold staff head representing an armed bird-man (fig. 9) (Jones: 58). But, north of the Tairona in Chiriqui, Panama (once part of Colombia) we find gold bat-man effigies holding an estolica (fig. 10).

In the Darien township, Cauca (see map below), one estolica from the Calima cultural zone was radiocarbon dated to AD 1200-1290 and was apparently made from the Chonta palm. It pertained to the late Sonso period (A.D. 1100-1600) when styles distinct from the earlier Yotoco culture (B.C.100-A.D.1100) are seen in the Calima area. The styles were so different that the Sonso people may have been immigrants from another area. This Sonso period estolica closely resembles what Krause calls the Brazilian type 2 estolica (Krause: 143) with a broadening of the shaft into a handle with a hole for the index finger. This defining characteristic is widespread in eastern South America (Spranz in Metraux: 159, 247). Only two examples of this type are know from Peru (Metraux: 246) since the usual Peruvian type is a stick with a hook similar to the Colombian “Andean style” instead of a hole for the forefinger.The Sonso period estolica (now 70.2 cms long with a 2cm diameter finger hole and 3.3cm at its widest part at the hole, then narrowing to 1.8cm for the long shaft) and parts of five darts (present shrunken sizes of three of the darts: 23.4cm, 33.7cm, and 42.6cms) (fig. 11) were found in a wooden coffin similar in design to some found in the San Agustin area dating about A.D. 425-1180. Similar wooden coffins have also been found in the Quimbaya area and in other valleys of the Central Cordillera (Reichel-Dolmatoff : 102. and fig. 19) (von Schuler-Schomig: 2:25-28). Mention of estolica use in the Calima area around the Cauca river (Rojas de Perdomo: 262) shows the diversity of dart-thrower use in Colombian climates varying from the freezing paramo to the pleasant (24 degree Centigrade) Calima area at 1,000 meters elevation above sea level. A spectacular gold estolica from the Yotoco culture measures 27.6 cms long (fig. 12) (Cardale de Schrimpff: 102). Similar gold estolicas with silver dart hooks have been found in Peru associated with the Moche culture (Marriner: Sept. 2000). Again, we find use, but no rock art representation of a dart-thrower in the Calima cultural area. One shrunken and distorted estolica and dart from the Quillacinga (A.D. 600-1600) cultural area of southern state of Narino(see map below), was found near the city of Pupiales, possibly around the 3,000 meter elevation (fig. 13).

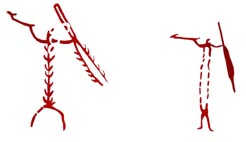

The style is similar to the Sonso estolica, but with a squared area around the finger hole (Marriner: 1999). Only by traveling south to the remote and nearly inaccessible region of the Chiribiquete National Park (see map below) do we finally find clear depictions of dart-throwers in Colombia on stone. Red pictographs on vertical rock faces portray anthropomorphic beings with darts in one hand and a dart-thrower in the other. The Chiribiquete park, crossing the tropical jungle-covered borders of the Caqueta and Guaviare states, not far from the Amazon River, contains at least 36 sites amongst large vertical precambrian and paleozoic rock formations (tepuys) covered with thousands of pictographs. Today, the karijona Indians inhabit this remote area 400-600 meters above sea level, but it is not known who painted the Chiribiquete pictographs. Carbon associated with exfoliated rock containing red paint has been dated to human occupation during at least 750 years from A.D. 500-1,250 (Castaño-Uribe: 36-39). These dates were associated with cult painting and not permanent habitation sites. There are positive indications that man was visiting this area as early as B.C. 3,600. Scenes possibly representing shamans hunting animals with estolicas abound in the pictograph sites. Some pictographs show the relation between man the hunter, and his prey, in what some call a sexual context (fig. 14).

According to the Colombian anthropologist Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff, hunting in the Amazon region is considered a type of courting, requiring the hunter to follow strict rules and procedures to seduce the animal, but only after a shaman has given the hunter his approval. Some of the most frequent rules and procedures are: sexual abstinence, vomiting, the use of aromatic plants, ritual cleaning of weapons, special diet, the use of tobacco and perfumes, amulets and magic spells. Behind all of this preparation, it should be noted that the hunter has been in training since childhood, learning the ways of the hunter and the hunted, special rituals, and gaining a profound knowledge of the life cycles and daily movements of many animals. Various Chiribiquete pictographs show anthropomorphic figures in the act of dancing and in rites accompanied by their estolicas and darts with up to 8 barbs (fig. 15). In summary, three dart-thrower weapon styles were definitely in use in Colombia between AD 500-1538, and possibly much earlier. Use has been documented from hot tropical Panama through the warm Calima cultural area in the state of Cauca, up through the savannah highland plains of the Cundinamarca-Boyaca region where the Muiscas lived, up higher to the Pisba paramo of the Guane, south to the mountainous area around Pasto, and then down into the Amazon jungle area of Chiribiquete where the Karijona live today. In Colombia, representation of dart-thrower use in rock art has only been discovered in the form of red pictographs in the remote region of the Chiribiquete Natural Park. Hopefully further investigations will uncover more evidence in the form of petroglyphs or pictographs.

—¿Preguntas, comentarios? escriba a: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com— Cómo citar este artículo: MARRINER, Harry . Dart-thrower use in Colombia and its representation in colombian rock art. en Rupestreweb, http:///rupestreweb.tripod.com/marriner.html 2000

BIBLIOGRAPHY -The author would like to thank Marianne Cardale de Schrimpff for her suggestions and loan of material, and Diego Martinez for his assistance with the graphics- Ardila Diaz, Padre Isaias. El Pueblo De Los Guanes: Raiz Gloriosa y Fecunda de Santander. Santander. 1978. Bray, Warwick. The Gold of El Dorado. Catalogue to accompany the exhibition. The Royal Academy, London. 1978. Bruechert, Lorenz W.. Mummy Burial of the Muisca Empire. Atlatl: The Newsletter of the World Atlatl Association, Inc. April 1998. Vol 11, No. 2. Aurora, Colorado. Cardale de Schrimpff, Marianne. Calima. Diez mil años de historia en el suroccidente de Colombia. Fundacion Pro Calima. pg 102 (MO24295). Bogota 1992 / Informe Preliminar Sobre El Hallazgo de Textiles y Otros Elementos Perecederos, Conservados en Cuevas en Purnia, Mesa de Los Santos. Boletín de Arqueología. Año 2, No. 3. Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Nacionales. September 1987. Castaño-Uribe, Carlos. editor. Parque Nacional Natural Chiribiquete: La Pergrinacion de los Jaguares. Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. 1998. Bogota) Castellanos, Juan de. Elegias de Varones Ilustres de Indias. Biblioteca de la Presidencia de Colombia. Vols. I, II, III, IV. Bogota. Editorial ABC. Bogota, 1955. Jones, Julie. The Art of Precolumbian Gold, The Jan Mitchell Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York. 1985. Krause, Fritz. Schleudervorrichtungen fur Wurfwaffen. Internationales Archiv fur Ethnographie. Band XV. Leiden 1902. P. 143. Tafel XII, 43; also Bodo Spranz. Die Speerschlender im Amerika. Veroffentlichungen aus dem Ubersee-Museum in Bremem, Reihe B, Band 1, Heft 2. Bremen 1956. p. 159. Tafel II. Marriner, Harry. Estolicas of the Colombian Muiscas. The Atlatl: The Newsletter of the World Atlatl Association, Inc. April 2000. Vol. 13, No. 2:1., Aurora, Colorado) /. Drawings of two Peruvian Moche culture gold and silver estolicas in a private collection were copied on 20 Sept. 2000. The gold shaft length was 38.4 cms for #1 and 38.5 cms for #2. Shaft diameter was 1.9 cms for #1 and 1.8 cms for #2. Weight of #1 was 52 grams and #2 was 51 grams. Both had a cap near the hook end a little wider than the shaft diameter. Four decorative bands were spaced along the shaft, one holding the silver hook and one for the cap / Marriner, Harry. Data taken in 1999 from a Quillacinga estolica in a private collection found c. 1989. Estolica shaft (present shrunken state) apparently of palm wood measures 1.3 cms diameter, 90cms overall length, with 1.5cm finger hole in a 4.5cm2 area located 33 cms from the shaft end. Hook was carved into the main shaft at 9.5 cms from the finger hole and 8 cms from the back tip of the estolica. Dart is serrated at tip for 19 cms. The dart shaft is 1.5 cms diameter and overall length is 32.5 cms. 1989. Metraux, Alfred. Weapons. Handbook of South American Indians. vol. 5. Washington 1949. Perez de Barradas, Jose. Los Muiscas Antes de la Conquista. Vol. 2, Instituto Bernadino de Sahagun. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Madrid. 1951. Plazas de Nieto, Clemencia. Nueva Metodología para la Clasificacion de Orfebrería Prehispánica. Jorge Plazas Editor. Bogota. 1975. Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Colombia. London. 1965. Rojas de Perdomo, Lucia. Manual de Arqueologia Colombiana. Carlos Valencia Editores. Bogota. 1979. Schottelius, Justus Wolfram. ‘Arqueología de la Mesa de los Santos’, Boletín de Arqueología 2 (3). Bogota. 1946. Simon, Fray Pedro. Noticias Historiales de Las Conquistas de Tierra Firme En Las Indias Occidentales. Vol. III. Ed. Banco Popular. Bogota. 1981. Uhle, Max. Uber die Wurfholzer der Indianer Amerikas. Mitteilungen de Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien, Band XVII., Wien 1887). von Schuler-Schomig, Immina. A Grave Lot of the Sonso Period. Archaologisch-ethnologisches Projeckt im Westlichen Kolumbien/Sud Amerika-Periodische Publikation Der Vereinigung. Pro Calima. Bogota Diciembre 1981.

[Rupestre/web Inicio] [Artículos] [Zonas] [Noticias] [Vínculos] [Investigadores] [Publique]

|